Crowdsourcing Content Guidance: A Commons-Based Approach to Harm Reduction in Theatre

by Sabrina Zanello Jackson

We must remember that institutional hierarchies remain intact as long as they are structurally powered, whether in a professional or educational context. If those in power wish to counteract these hierarchical pressures, providing content warnings before being asked is an excellent way to demonstrate openness and compassion.

The Problem: “Suffer for Your Art”

In the three years before my mother passed of cancer, I became more careful about engaging with stories of death. In 2021, I read Julia Izumi’s miku, and the gods. (2021). I had heard so many praises of the play that I didn’t bother to review its Subject Matter Keywords on the New Play Exchange (NPX), which prominently include “grief” and “coming to terms with death.” When the folkloric comedy about friendship, adventure, and Sumerian gods that I had anticipated turned out to be a profound exploration of death, grief, and ancestry, I was shaken. I sobbed all night and woke the next morning to eyes swollen half-shut. I don’t regret reading the play, but I do regret not reaching out to friends for content warnings beforehand. Bracing myself before reading would have let me engage the text dramaturgically while shielding myself from the ultra-personal.

Content guidance—alternatively called content “warnings,” “disclosures,” or “advisories”—can benefit anyone, including artists. A fellow dramaturg, GG, confided: “I cannot stand stories where an animal dies. When possible, I search DoesTheDogDie.com beforehand. If there’s a chance of that happening but I don’t know for sure, I won’t engage with the narrative at all.” Content advisories empower GG to engage with more content and do so with greater attentiveness, rather than be distracted by their anxieties about the unexpected.

Have you ever turned down watching a horror movie because it was too late at night? Content guidance can guide our choices based on mood or readiness. “I don’t have any specific story, other than that every time I go to see a show, I feel empowered by content warnings,” Stephen,[iv] an actor, told me. “For example, am I prepared to see the embodiment of a sexual assault? Is that something I want to see on my Friday night?” While the discourse on content disclosures often focuses on ableism-ridden descriptions of survivors or neurodivergent people, content warnings are useful regardless of ability or trauma.

More theaters are recognizing the value of content warnings for audiences, but their importance for theatre-makersis still overlooked. The “tortured artist” myth persists. Great art is born of greater suffering. On the contrary, storytellers can benefit from content guidance as much as spectators. By not providing content guidance from the impetus of creative work, theatre institutions and educational theatre programs alike exclude artists with Madness/mental illness, neurodivergence, sensory differences, and trauma and subject them to unsafe working conditions.

When arts organizations do not routinely provide content guidance in advance, they require individuals to come forward and request it. This can mean someone having to explain their trauma or come out as disabled for their request to be validated. Writer and Disability Justice organizer Mia Mingus describes this as forced intimacy: “the common, daily experience of disabled people being expected to share personal parts of ourselves to survive in an ableist world,” (Mingus 2017). Until arts and educational institutions normalize content warnings as a tool beneficial for everyone regardless of ability, and provide them proactively, artists with disabilities and/or trauma will be “expected to ‘strip down’ and ‘show all of our cards.’” In other words, discarding harm prevention/reduction methodologies makes it difficult for everyone to communicate consent—doubly so for disabled folks.

In the educational setting, requiring students to individually request content warnings can be a monumental access barrier due to the power dynamic between instructors and students. Students may fear retribution from their professors. This is doubly true for students of marginalized identities who face higher levels of scrutiny under ableist, white supremacist, and cisheterosexist systems. Just as Mingus asserts that “able-bodied people will not help you with your access unless they ‘like’ you,” Minor Feelings author Cathy Park Hong emphasizes that students of color often feel obligated to achieve at higher standards than their white peers (Hong 2020, 32). If a student felt pressured to project “anonymous professionalism,” and not “take up space nor make a scene,” they would likely feel discouraged from proactively bidding for care. We must remember that institutional hierarchies remain intact as long as they are structurally powered, whether in a professional or educational context. If those in power wish to counteract these hierarchical pressures, providing content warnings before being asked is an excellent way to demonstrate openness and compassion.

In response to the premise that the impacts of Madness/mental illness, neurodivergence, sensory differences, and trauma are not “severe,” I contend that we shouldn’t only care about people’s wellbeing when there is risk of serious physical or psychological damage. When interviewed for a video on Transformative Justice, Mia Mingus expressed:

I think a lot of harm that happens is like death by a thousand cuts. And we often don’t pay attention until there are so many little cuts that we’re bleeding out. And then we rush… to the crisis and the emergency and we drop everything. But what if we started dropping everything when the little cuts happen? (Project NIA and the Barnard Center for Research on Women 2020)

Content warnings represent this exact opportunity. Let’s move to a culture of care from the beginning of our theatrical processes, whether that be uploading a new play to NPX, writing script coverage, or kicking off a production timeline.Granted, content guidance is only one small part of harm prevention/reduction, but it is a worthy place to start treating those “little cuts.”

What if submitting content warnings only meant a few extra clicks?

I believe one way to address our problem is to build a living, crowdsourced database of script content warnings for the theatre community. A recurring sentiment from critics is that implementing content disclosures requires unreasonable time and effort, at the expense of other work. Some script readers include content warnings in their coverage, but coverage is an inherently closed-door practice and varies by organization. With a crowdsourcing tool, content guidance could make it out of the rooms where literary management and season planning happen and into public service. The work is already happening, so why not put it to sustainable use?

In 2012, Gwydion Suilebhan dreamed up a centralized script repository to connect playwrights with producers (Suilebhan 2012), which catalyzed the birth of the New Play Exchange (Loewith and Suilebhan 2016). Similarly, this note from the field seeks to function as my concept for a crowdsourced content guidance database, exploring my prototyping process thus far and laying out the strengths and gaps of the current vision. I encourage readers to reach out with feedback or to get involved.

A New Future: Crowdsourcing Content Guidance

I envision this commons-based approach being used on a global scale, making content warnings accessible online as easily as a plot synopsis. The intention is to provide a four-fold solution:

1. Provide support before the need arises, modeling access intimacy (Mingus 2011)

2. Archive this labor to reduce redundancy

3. Allow for multiple perspectives on the same play, modeling a culture of abundance

4. Cultivate a shared vocabulary for discussing sensitive content

The crowdsourcing tool has had two conceptualizations to date: the first practically, the second theoretically.

A Brief Summary of Iteration 1.0

In 2021, I prototyped a database of playscript content advisories crowdsourced by and for my conservatory theatre program. All students, faculty, and staff were encouraged to (a) submit content warnings for a script they read for any reason (education, work, or pleasure) and (b) search the database for a play before reading it.

Content guidance was submitted via a Google Form, which organized content into six major categories: (1) strong or insensitive language, (2) nudity, (3) romantic or sexual intimacy, (4) sexual violence, (5) graphic violence, and (6) illness or trauma. Categories were meant to make it easier for people to submit warnings and to expedite database navigation. Each category was subsequently divided into “mentioned in the text” and “depicted on stage” (Figures 1–2).

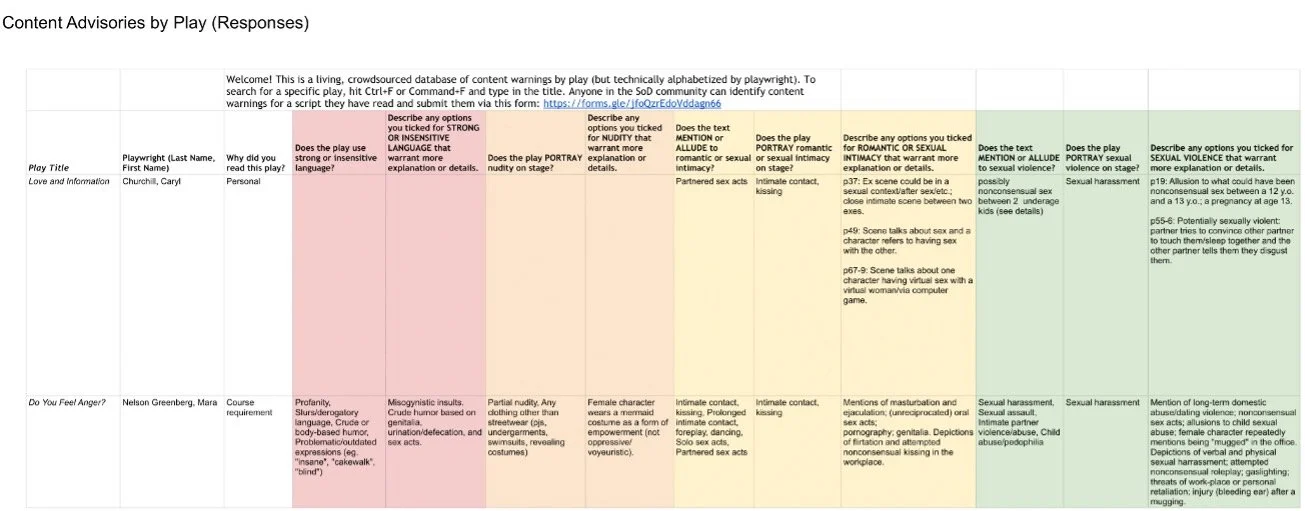

Form responses were automatically added to the Google Sheet (Figures 3–4). The Sheet was alphabetized by playwright’s last name, making it easy for users to search via the hotkey Control+F or by scrolling.

As the length of the spreadsheet shows, balancing thoroughness with expedience was difficult. I made every question optional except for the first three—play title, playwright name, and in what context the script was read—but the length still proved a barrier. Of the twenty-some individuals who graciously beta-tested the database, many found the form overwhelming and felt discouraged from completing it.

In summary, 1.0 was limited. Its clunky format and narrow, transient user base of university members rendered it unsuccessful. Although Google Sheets is beneficial because it is accessible to anyone online, it can only handle so much data and its opportunities for data visualization are few. Above all, the fact that it was isolated from the platforms on which people read and review scripts made it ineffectual.

Concept for Iteration 2.0

This iteration takes a new approach as a tag system built into a custom website. This way, the database would be easy to access and quick to use. A tag is a nonhierarchical keyword that describes the data that it is assigned to. Tags are useful for classifying information in multiple ways simultaneously. Ideally, the tag system would be also integrated into existing cloud-based script libraries such as the New Play Exchange, Drama Online, and Alexander Street Drama.

2.0 is largely inspired by two highly trafficked platforms that crowdsource content guidance, among others (see the end of this field note for a list). Firstly, the community-driven website and smartphone application Does the Dog Die? houses an extensive database of warnings for film and television, among other media (Wipple 2010). It is remarked for its democratic Upvote/Downvote feature and for making detailed spoilers and even time stamps available to site visitors (Lindbergh 2020). Secondly, The StoryGraph, a data-oriented book tracker and competitor to Goodreads, prominently offers users the ability to tag content when submitting a book review and filter for content when searching for new reads(Herman 2021). The latter is particularly exciting because of its similarities to the New Play Exchange: powered by metadata, encouraging dialogue, and inviting the engagement of authors themselves (Odunayo and Frelow 2019).

The StoryGraph also models a cautionary tale. Recent discourse highlights how content warnings have been weaponized to censor books by writers who are of color, LGBTQ+, or otherwise marginalized. In 2021, author Sylvia Moreno-Garcia sparked debate on X by pointing out how books by authors of color are tagged for sensitive content more often than books by white authors on The StoryGraph (Figure 5; ad astra 2021).

Unconscious bias plays a hand in this double standard. A white script reader may fail to pick up on underhanded manifestations of racism or overestimate race’s prevalence in a story. Science fiction author Octavia Butler wrote an entire afterword to Bloodchild to address that the extrasolar short story is not about slavery, contrary to popular interpretation (Butler 1995, 55-57). But Moreno-Garcia sees this as not only an individual issue, but one systemically reinforced by data-collecting cyberspaces. “Review spaces are not free of such biases. Neither are TWs. I’m not going to say this means there are ‘bad’ and ‘good’ reviewers because that’s not what I was going on about,” she elaborated in a follow-up tweet (Moreno-Garcia 2021). The ensuing debate prompted The StoryGraph to launch author-approved content warnings and a summary smart filter, which we’ll explore later (The StoryGraph 2021). Given this backdrop, we must consider how crowdsourcing content advisories for plays might affect marginalized playwrights.

With the insights and a notable dilemma of these platforms in mind, let’s explore possible features of the 2.0 crowdsourced database.

Submission

Following The StoryGraph’s methodology, there would be two sections of content guidance: playwright-approved and reader-submitted. Allowing playwrights to add advisories gives them agency over the narrative being constructed about their work without censoring the perspectives of readers who may experience the text differently. If built into NPX, it would bolster the platform’s commitment to amplifying playwrights’ voices (Loewith and Suilebhan 2016). Readers would submit advisories as part of their script recommendations or via an independent function, increasing engagement on the platform.

Types of Content

Moving away from categories to a singular alphabetized list of tags, as The StoryGraph models, holds space for specificity and intersectionality. Both qualities bolster consent work. The list of tags below was mainly sourced from The StoryGraph, with some language pulled from the Trigger Warning Database (Lilley and Typed Truths 2017), Does the Dog Die?, Unconsenting Media, “Defining Mental Disability” (Price 2017), and harm reduction best practices (National Harm Reduction Coalition 2021):

· Abandonment

· Ableism

· Abortion

· Acephobia/Arophobia

· Addiction

· Adult/minor relationship

· Alcohol

· Alcoholism

· Animal cruelty

· Animal death

· Antisemitism

· Biphobia

· Blood

· Body horror

· Body shaming

· Bullying

· Cancer

· Cannibalism

· Car accident

· Child abuse

· Child death

· Chronic illness

· Classism

· Colonization

· Confinement

· Cultural appropriation

· Cursing

· Deadnaming

· Death

· Death of parent

· Dementia

· Deportation

· Disordered eating

· Domestic abuse

· Drug abuse

· Drug use

· Dubious consent scenarios

· Dysphoria

· Eating disorder

· Emotional abuse

· Excrement

· Existentialism

· Fatphobia

· Fire/Fire injury

· Psychiatric institutionalization

· Gaslighting

· Genocide

· Gore

· Grief

· Gun violence

· Hate Crime

· Homophobia

· Incarceration/Imprisonment

· Incest

· Infertility

· Infidelity

· Injury/Injury detail

· Intimate partner abuse

· Islamophobia

· Kidnapping

· Lesbophobia

· Mass/school shootings

· Medical content

· Medical trauma

· Mental illness

· Miscarriage

· Misogyny

· Murder

· Nudity

· Outing

· Pandemic/Epidemic

· Panic attacks/disorders

· Poverty/Houselessness

· Pedophilia/Grooming

· Physical abuse

· Police brutality

· Pregnancy

· Racial slurs

· Racism

· Rape

· Religious bigotry/persecution

· Schizophrenia/Psychosis

· Self-harm

· Sexism

· Sexual assault

· Sexual content

· Sexual harassment

· Sexual violence

· Slavery

· Slurs/Derogatory language

· Stalking

· Suicidal thoughts

· Suicide

· Suicide attempt

· Surveillance/Being watched

· Terminal illness

· Torture

· Toxic friendship

· Toxic relationship

· Trafficking

· Transphobia

· Unstable/shifting reality

· Violence

· Vomit

· War

· Xenophobia

In addition, the crowdsourcing system could meet individual needs by allowing users to flag tags for content they particularly wish to avoid in their profile settings (Odunayo and Frelow 2019).

Intensity and Staging Fields

When submitting content warnings on The StoryGraph, reviewers select tags from three drop-down lists, each representing a tier of intensity: Graphic, Moderate, and Minor (Figure 6). For the theatre community’s purposes, let’s keep this system and add a fourth, independent field called “Staged.” This would classify content that requires on-stage depiction for the audience to follow the story. There is a vast emotional difference between a character describing a death and a performer acting out death on stage. And while nudity may not be inherently sensitive in literature, it is when staged before a live audience. For example, consider How to Defend Yourself by Liliana Padilla. Seven college students gather for a DIY self-defense workshop after a sorority sister is raped (2020). Sexual assault and processing its aftermath make up the emotional core of the story, but the audience is never witness to a simulated sexual assault. The system would allow the same tag to be input into the Staged field and an intensity field, giving perusers a fuller impression of the content.

Specifying what content is depicted on stage would fit well with the benefits that users reap from the New Play Exchange’s robust search-and-filter mechanism (National New Play Network 2015). Many use the platform to find scripts to produce, and filters allow them to search with their unique production parameters and resources in mind. Tagging content that must be staged for the audience to follow the story—whether nudity, violence, sex, etcetera—would allow readers to proceed knowing they should plan for an intimacy choreographer and other production safeguards, or else creatively circumvent a direct portrayal. If someone can’t manage that, they can use the search filters to exclude plays with certain Staged tags. Best of all, this would reduce the cases of such content going unnoticed and unaddressed until it is too late in the production process.

Custom Details and Spoilers

If any content falls outside the existing tags or warrants qualification, submitters would be able to add detailed descriptions as comments attached to relevant tags. DoesTheDogDie.com users can toggle in their settings whether they wish for comments to default as visible or hidden (shown on click), so they can avoid stumbling upon spoilers unintentionally (Staublin 2022).

The StoryGraph goes a step further, requesting that users wrap any spoilers in programming tags as follows: <spoiler>your spoiler text</spoiler>. Once one’s review is submitted, the spoiler text appears blacked out and is revealed only if a user clicks on it (Figure 7, available in the PDF). This is an elegant solution for one of the most common concerns voiced by opponents of content guidance.

Data Amalgamation

Displaying the tag system’s aggregate data would encourage a nuanced critical discourse among users about potentially intense or triggering material. It would also foster a culture of abundance in which all opinions are valued. Balancing brevity with completeness, The StoryGraph provides a summary and a complete list of content warnings. Figure 8 (available in the PDF) shows how the platform automatically smart-filters the top three most selected tags for each intensity tier.

The algorithm is complex: it generates the summary based on the number of votes a tag receives and its comparative prevalence across intensity levels. A tag must have at least twenty votes to be eligible but cannot have more votes under another level of intensity.

Clicking “See All…” opens the full list of author-approved and user-submitted content warnings (Figure 9). Each tag includes a parenthetic number indicating how many people selected that content. These numbers would equip prospective script readers with knowledge of the majority and paint a picture of the nuances and varying perspectives on the same story. If thirty people tag war as Moderate while twenty-five tag it as Minor, its intensity may be dramaturgically debatable. Additionally, this data would make the crowdsourcing tool’s inner workings more transparent to site visitors.

Ancillary Resources

An educational guide to content guidance and consent work would accompany the crowdsourcing tool. It could include a glossary of key terms, best practices, and extended explanations of the intensity tiers (Graphic, Moderate, and Minor) and the Staged field to better assist users with categorizing content (Payne and van Staden 2017). In an ideal world, this information would not be an external link but integral to the webpage as a collection of tooltips—question marks ⍰ and information icons 🛈 that reveal more details when hovered over (Rodricks 2021).

Considerations for Future Work

Much more dreaming is needed, with many more voices, before this project is prototyped again. Below are a few quandaries at the forefront of my mind.

Draft Updates

What happens when a living playwright shares a new draft of their script? The content warnings submitted before that upload may become outdated. How might the database account for that, or does this issue undermine the whole concept of crowdsourcing for any new plays?

User Feedback

What metrics should we use to assess the project’s success? How might end users be able to give feedback on the database once it’s prototyped and even published? Providing an accessible, anonymous channel for feedback will be key to honoring the project’s commons-based approach and mitigating forced intimacy.

Anonymity

Should users have the option to submit content guidance anonymously? Although anonymity would mitigate forced intimacy, its ramifications within a transparent, community-focused platform are ambiguous and potentially troubling.

Self-Selection Bias

Participation bias will skew the data of content tags. By what means might the tag system account for this?

Biased Censorship

Earlier, this note discussed how the disproportionate use of content warnings inadvertently contributes to censoring marginalized authors. Censorship in the theatrical context could mean prematurely rejecting a play from option. What features could be implemented to counteract disproportionate tagging and its result, biased censorship?

Conclusion

Content guidance is not only vital to the wellbeing of theatre-makers with disabilities or trauma, but contributes to a culture of trust, care, and consent that benefits everyone. A database of script content warnings would amplify the discourse around trauma-informed practices and reduce the labor of crafting warnings from scratch in the long run. A commons-based approach offers education and reduces shame. Gone would be the grievance among arts administrators and educators of feeling ill-equipped to write content warnings. I myself often feel unsure how to write them, but the support of a framework and language empowers me to do so. Even more, knowing that others will contribute different interpretations of a text makes me less worried about identifying content “incorrectly.” Disclosing some content is better than none. Making content guidance a community effort via dialogic platforms would nuance the discourse about a play and empower prospective readers with an abundance of viewpoints.

Although this database concept is flawed and leaves gaps unaddressed, I am convinced that even such imperfect, work-in-progress efforts help gradually shift institutional culture.

Call for Collaborators

This paper only represents the beginning of this project. To anyone reading this, thank you. A community-driven database should be designed in community, so I eagerly invite those interested to join the endeavor. Whether you share a passion for disability-informed, consent-forward initiatives, are a programmer or user experience wiz, or have a hot take, please reach out. Collective engagement propels this work forward.

Non-Exhaustive List of Crowdsourced Content Warning Databases

· Does the Dog Die?: With over 29,000 titles, it is overwhelmingly used for film and TV, but also books, video games, comics, podcasts, YouTube, and more. Data-driven and community-run (submission automatically affects the data).

· The StoryGraph: Book reviewing and tracking platform with a built-in content warnings tag system. Data-driven and community-run.

· Trigger Warning Database: For books. Data-driven and moderated (site manager manually processes submissions). The administrative account is also active on Goodreads, where it ‘shelves’, or tags, books by content.

· Musical Content Warnings: A small hub on Tumblr for musical theatre. Not data-driven (submissions are free response) and moderated.

· Unconsenting Media: For sexual violence in film, TV, and more. Data-driven in a simplified way and volunteer-moderated. It also began as a humble Google Sheet (Payne 2017). Does the Dog Die? creator John Whipple helped the site get started, largely by importing DDD’s structure (Norris 2022).

Footnotes, photos, and references available in the PDF