Intimacy in Improv: An Account of the Use of Consent-Based Practices in Non-Scripted Theatrical Explorations

by Joshua Richardson

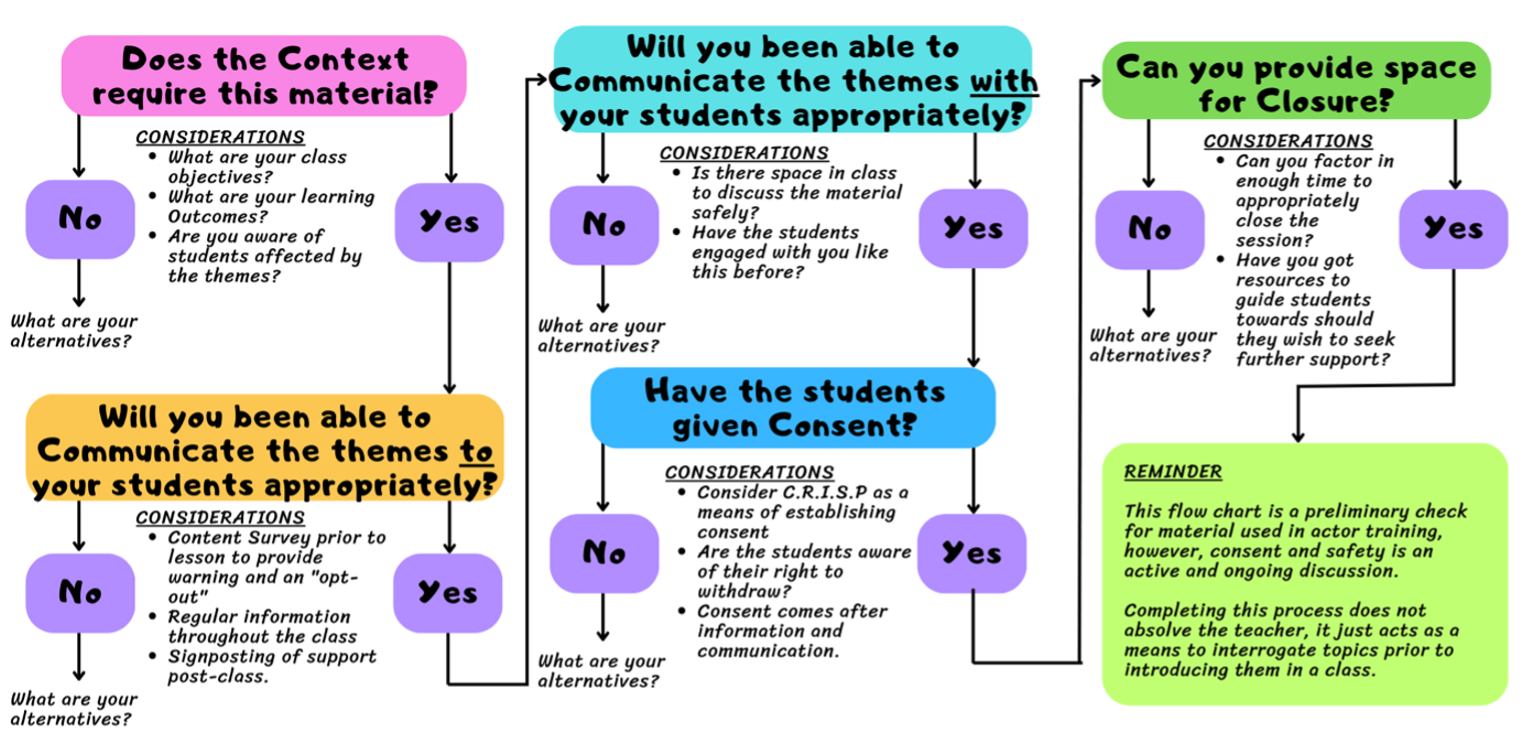

“Figure 1 is a flow chart I created to ensure I can respect the boundaries of my students. This was inspired by my... research into Trauma-informed pedagogy, as a means of “actively resist[ing] re-traumatisation” (Columbia University 2023). It is designed to function as a Consent-focused, re-traumatisation prevention method. ...The following is an example of how I have actively engaged with the flow chart. ”

As an actor trainer in higher education contexts, I have noticed that almost every class I have taught or have been a student in has contained some form of non-scripted or improvised element. This could be pure improvisation, physical exploration, or active analysis. There are a multitude of methods that we use to create, explore, and play, but far fewer to ensure student safety while doing so. In this note from the field, I will discuss some of the systems I use to mitigate the risk of a student’s boundaries being breached, whether that be by another student in the space, or myself as the facilitator and educator. I will also be nodding to other theories of consent, intimacy, and trauma-informed pedagogy that inspired me to create these systems and synthesise them into my practice.

To provide more context on my practice and the creation of these tools, I will delve into the methodologies, pedagogical theories and philosophies that have inspired me. I hope this will further contextualize the student-centred approach I employ as a facilitator, director and pedagogue in actor training spaces. The incorporation of these frameworks stems from my experiences as a Queer-identifying student and teacher within largely heteronormative drama training institutions and the wider experiences as a Queer identifying body within the contemporary reality I am situated in.

bell hooks is a radical feminist pedagogue, author, theorist, educator and social critic whose work has been pivotal in the development of my practice. Within their writings they often refer to the building of a “learning community” (hooks 2010) and the call for recognition of everybody in the learning environment. hooks says:

The call for recognition of cultural diversity, a rethinking of ways of knowing, a deconstruction of old epistemologies, and the concomitant demand that there be a transformation in our classrooms, in how we teach and what we teach, has been a necessary revolution – one that seeks to restore life to a corrupt and dying academy(hooks 1994)

I first came across this quote when interrogating the concept of “neutral” within actor training practices. My research found that the traditional sense of “neutral” often equated to an erasure of self and was inherently problematic. Nicole Brewer discusses this by saying: “Asking students to constantly disregard race, cultural context, perspective, and history in their training implies that white cultural identifiers are the default, and non-white identifiers have no inherent value and therefore should be suppressed.” (Brewer 2018).

This can also be said for those that have experienced trauma linked to homophobia, racism, gender discrimination or other prejudices based on a person’s alignment with a subjugated or marginalized group. By ignoring the presence of this experience and telling them they “shouldn’t come to theatre with muddy feet […] which complicate your life and distract you from your art” (Stanislavski 2008), we are implying that a student’s lived experience holds no inherent value and should not be considered as part of their training experience.

In recognizing students’ identity and lived experience in the space, I am actively engaging with anti-racist and feminist methodologies by providing space for students in the room to bring their whole selves. By actively recognizing my students as having existed prior to entering my rehearsal space and welcoming their “muddy feet” (ibid 2008), I am already taking the first step into trauma-informed pedagogy. My cognizance of potentially negative lived experiences means I can “actively resist re-traumatisation” (Columbia University 2023) by making decisions and accommodations based on the humans I have welcomed into the training environment.

By adopting bell hooks’ call for a transformation in how and what we teach we are actively engaging with Matthew Thomas-Reid’s descriptions of Queer Theory: “Queer theory may help challenge normative assumptions and social practices to build a conceptual bridge between bullshit and authenticity. If to make things queer is certainly to disturb the order of things” (Thomas-Reid 2020).

I argue that this “conceptual bridge” is being built by recognizing the student in the space, thus recognizing their authenticity, and not requiring them to “bullshit” through the practice of hiding parts of themselves that may be painted as not welcome or not valuable. Additionally, my challenges the “normative assumptions” (Thomas-Reid 2020), that in a pedagogical environment can be considered the “unavoidable dynamic” (Symonds 2021) where teacher is viewed as the “unilateral authority” (Symonds 2021). This intentional disruption through the centring of students allows for informed decisions around the exercises and subject-material that I bring to the class. Here, I aim to discuss how and why I take these steps to ensure that a learning environment–particularly one that engages in the art of improvisational performance–can be as safe as possible for students.

Firstly, I interrogate the material I might bring to class. This interrogation is inspired by the “five Cs of intimacy” as put forward by Siobhan Richardson and Intimacy Directors International, prior to its rebranding to Intimacy Directors and Coordinators (Morey 2018). These “Cs” are considered pillars of intimacy coordination and should all be present when working with actors to direct intimate scenes. They are: Context, Communication, Choreography, Consent and Closure. In integrating these pillars of Intimacy practice into my teaching, I am able to reflect on my choices as a pedagogue, and how they may impact the students. The only “C” I don’t engage with is Choreography, due to this process taking place prior to student interaction.

Figure 1 is a flow chart I created to ensure I can respect the boundaries of my students. This was inspired by my previously mentioned research into Trauma-informed pedagogy, as a means of “actively resist[ing] re-traumatisation” (Columbia University 2023). It is designed to function as a Consent-focused, re-traumatisation prevention method. By recognizing that selecting relevant material as a starting point and communicating that with your students lessens the potential for participants in the class losing agency or autonomy, I can prevent the content that I provide from activating or triggering students. The following is an example of how I have actively engaged with the flow chart.

I was preparing a Scene Study module, in which students would be taught concepts such as “beats, units, objectives and super-objectives” (Merlin 2016) and use their study to rehearse and perform a scene. I tried to find one play that the students could each pick specific scenes from. I considered the stage version of Brokeback Mountain by Annie Proulx and Ashley Robinson. In the context of the module, the several moments of intimacy seemed unnecessary. This is due to the consideration that to understand the concepts of scene study and meet the module learning outcomes, a student does not need to portray intimate scenes; thus, they are not required in this context.

Instead, I considered Nick Payne’s Constellations, A play with two characters that flips between multiple universes. The play handles scenes of grief and talks about death, love and facing one’s own mortality. Being aware of these themes, the next step was to communicate this to, and then with, my students. The important difference between toand with is: first I informed, then I invited the student actors to become an active part of the discussion. This is vital, not only because it falls under the “Participatory” part of the “C.R.I.S.P”[i] acronym (Intimacy Directors and Coordinators 2023), which will be discussed later in this article, but it also facilitated moving to the next stage of the flow chart: consent.

During my discussion with the students, I was able to introduce my choice and provide information regarding themes and content that are found within the text. After providing this information, students were able to communicate if they felt prepared to engage with the choice I had made. Additionally, I informed the students of how the lessons around the text would take shape and their option to withdraw their consent to approach this material at any time during the process.

Finally, I explained the process of closure I would utilize at the end of each future session. In my experience, an opportunity to reflect on the session, and maintaining a structure to the end of my sessions, provided students with enough time to feel as if the session was closed and aided in the prevention of emotional hangover: “the feeling of being drained after leaving an emotionally taxing environment or event.” (Gillis 2023). The time to reflect also provided an opportunity to respond to any concerns the students had after exploring the text, by sign-posting additional resources to them. These additional resources would either be mental health support provided by the institution or outside organizations, phone numbers linked to additional supportive resources, or information on approaching for further support.

By following this process, I try to ensure that my students can explore this text through improvisational means such as active analysis, described as a way for “actors [to] test their understanding of how characters relate to and confront each other through improvisations of scenes in [a] play” (Carnicke in Hodge 2010).

In my experience using this method, I have found that students are often happy with initial choices and, through being a part of the conversation, have a greater understanding of how I arrived at the decision to select a particular script. In being part of the process, students are able to exact a certain level of control and autonomy which is vital in trauma-informed pedagogy as at “the heart of trauma is a sense of powerlessness and disconnection” (Thompson and Carello 2022). This process of communicating with and to the students provides a sense of control and connection to their academic journey.

On the occasions when students have been uncomfortable with a chosen text, the simple act of providing a channel through which they can communicate their concerns and have them heard has benefitted students’ progress in the class. A previous student came to me to discuss how some references to sex and sexuality made them uncomfortable in a text that was chosen. They were okay with watching scenes that contained that type of material but would rather not participate in one. To remedy this, I simply made offers of other scenes from the same script that they could choose from. After having that discussion, I noticed a major improvement in the student’s participation in my classes, even across other modules. They were more engaged in exercises, spoke more openly within reflections and made some excellent offers within the space.

It is hard to attribute this improvement solely to that one interaction, but I argue that due to the knowledge that they had the ability to voice concerns and have those concerns heard and acted upon, the student-teacher dynamic was strengthened with trust. “When you trust someone to do something, you rely on them to do it, and you regard that reliance in a certain way: you have a readiness to feel betrayal should it be disappointed, and gratitude should it be upheld”(Holton 1994).

As “students who have experienced trauma may have difficulties trusting others due to their past experiences” (+ProActive Approaches 2023), being able to develop trust in this way is vital for an educator. This is an integral part of the Queer methodology I incorporate. I aim to create a space where students are comfortable advocating for themselves and allow them to engage with their “authenticity” (Thomas-Reid 2020). Even with these precautions the question still remains, how does one ensure that students' consent is maintained during non-scripted or improvisational exercises?

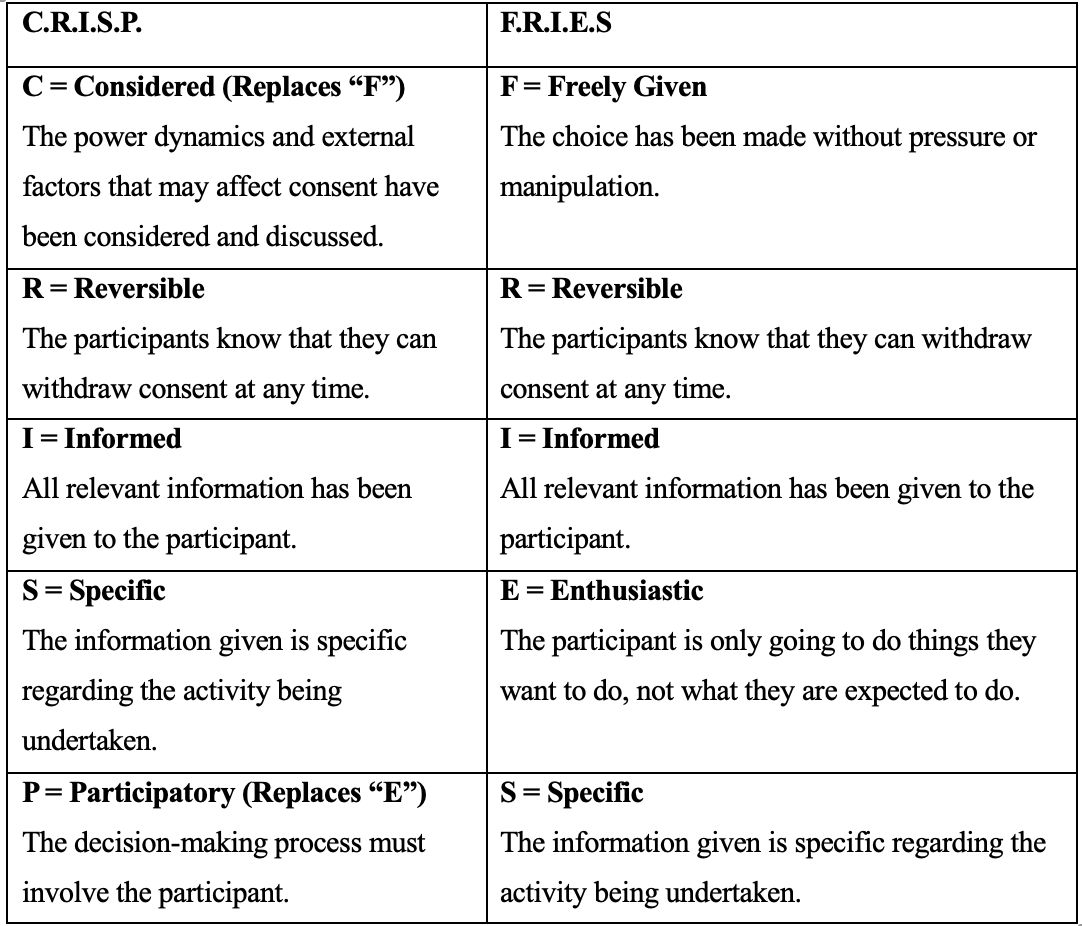

In all of the choices I make in my approach to actor training, C.R.I.S.P is at the heart of all of them. C.R.I.S.P stands for Considered, Reversible, Informed, Specific and Participatory. This acronym created by Intimacy Directors and Coordinators (Intimacy Directors and Coordinators 2023) is a performance-specific version of Planned Parenthood’s F.R.I.E.S acronym (Planned Parenthood 2023). The table below names and compares the two.

Intimacy Directors and Coordinators argues that because of the power dynamic often present during rehearsals, consent can never truly be “freely given” or “enthusiastic,” thus replacing those with “Considered” and “Particpatory.” This is due to the coercive power held by directors. Coercive power is “A person’s ability to influence others’ behaviour by punishing them or by creating a perceived threat to do so” (Lunenburg 2012). It is important to highlight that the definition specifies a “perceived threat to do so,” which I point out because I am not suggesting all directors will punish an actor if they say no; however, the presence of fear created by previous negative experiences or previously heard anecdotes is enough to affect true consent being given.

The consideration of previous negative experience links not only to Trauma-informed pedagogy and the concept of “actively resist[ing] re-traumatization” (Columbia University 2023), but also to what Eloise Symonds describes as “the traditional learner” (Symonds 2021). “The traditional learner” is a term used to describe undergraduate students who “depend on the unilateral authority of the teacher,” a role which has been “socially and historically constructed by a specific culture” (Symonds 2021) which is prevalent in UK Compulsory education.

This creates a power asymmetry, which has been described as an “unavoidable dynamic” (Symonds 2021), where the students perceive the lecturers hold the following bases of power:

· Legitimate Power: “a social norm that requires that we obey people who are in a superior position in a formal or informal social structure” (Raven 2008).

· Expert Power: “based on an individual’s advanced knowledge about a project, a given field or some other specialty, based on education and/or experience” (Kovach 2020).

· Reward Power: “The ability of a person to provide someone with the things which he desires and to remove those things which he does not desire.” (Faiz 2013).

Being cognizant of the powers that I hold as a teacher means that ensuring that students are actively consenting throughout, not just “doing it because the teacher told me to”. This is an ongoing process that I scaffold into my lesson plans using introductory exercises and frequent reminders of their own autonomy.

One example of how I do this, is incorporating Justin Hancock’s and Meg-John Barker’s exercise called “The Three Handshakes” (Hancock 2015) into the introduction of my lessons with a new cohort of students. The exercise involves asking students to walk around the space participating in three rounds of handshakes. The instructions for each round are:

1. Shake hands with everyone you walk past.

2. Shake hands with everyone you walk past, but negotiate it. (i.e. Would you like to shake with the left or right hand?)

3. Shake hands with everyone you walk past, but negotiate it without verbal communication.

The purpose of the exercise is to encourage the students to engage with negotiation in non-scripted scenarios. I use it as a tool to introduce concepts of consent and paying attention to ways in which we communicate beyond the verbal, acknowledging that a person may express discomfort without saying “I’m uncomfortable.”

When using this exercise, I have noticed not only a development in the students’ awareness of the boundaries of their scene partners, but also a greater attention to the scenes themselves. When teaching improvisation specifically, I engage with Adam Meggido’s three principles of “listening, accepting, commiting” (Meggido 2019). Meggido describes these three principles in more detail in their book, Improv Beyond Rules, but the following quotes provide a snapshot of each concept’s ethos:

· “Listening is a willingness to be changed”

· Accepting is to give a ‘real yes’, which is “to be affected by the offer”

· Commiting is acknolwedging that “there is nowhere to hide” from an audience and that you should “perform with commitment” (Meggido 2019).

When you consider negotition as “the process of discussing something with someone in order to reach an agreement” (Cambridge Dictionary 2024), the links to the three handshake game and Meggido’s three principles become apparent. Students are required to listen to the offers made, accept the boundaries of the person they are working with, and commit to respecting those boundaries in conjunction with their own. By instilling a sense of negotiation from the start of the session, I have already begun scaffolding Meggido’s concepts alongside the concepts of boundaries through this framework. This may not be necessary if using this game in other contexts, but considering how all improvisational exercises, such as active analysis, can stand to benefit from a deeper understanding of improv and consent, it is certainly welcome.

In other classes where Improv is not the focus, I have found that students are able to communicate the feeling of negotiation articulately, but often with a focus on acting methodology. They often talk about “listening to one another,” “adjusting to my scene partner” and “connecting” (Anonymous Student 2023). These valuable inputs allow me to “relat[e] their previous learning to their current experience of the world, directly linked to their epistemology” (Diaz 2017). The benefit of this is that the concept of consent and boundaries is approached with senstitivity and related to their prior knowledge of the actor training environment. For example, the idea of “adjusting to [their] scene partner” can be linked to their engagement with consent and allows us to interrogate the question: When someone sets a boundary or doesn’t consent to an action, what steps do we take to adjust or accommodate?

In addition to this, I’ve incorporated the practice of self-care cues into the initial scaffolding of my lessons as a stop-start mechanism. This acts as a mode of communication for the students where they previously may not have had the tools to remove consent. This practice was inspired by the work of Amanda Rose Villarreal and their rehearsal processes in the realm of immersive performance, and their work related to LARP-ing, or Live Action Role Playing (Villarreal 2021; Villarreal 2023).

Live Action Role Playing actors are often customer/audience facing. In these scenarios the unpredictable nature of improvised interactions paired with non-trained participants has the potential to leave actors in precarious positions. I personally have encountered customer interactions, when doing crowd work for a queue of people in which people have assumed that because I am performing, my autonomy is irrelevant. In this work, customers often touched me or invaded my personal space without fair warning or consent being established.

To provide a safety mechanic for the actors, Villarreal scaffolded the self-care cue “rebels” into their rehearsal processes. The actors were taught to listen out for that word from other actors, as it was an indicator that their cast mates were feeling unsafe or uncomfortable. They would intervene with support or a gentle suggestion to the customers to move on to another part of the experience (Villareal 2023). As the self-care cue related to the world they had created, Villarreal reported that students felt “empowered to establish boundaries without ‘ruining’ or interrupting the performance” (Villarreal 2023).

The inspiration from the world of LARP-ing led me to incorporate a similar edition of the stop-start mechanism, without the component of not “interrupting the performance,” as this would require establishing a new safe word for every different world that we create within the space. Instead, I offer British Sign Language (BSL) signs that students can use at any point within the class to remove themselves from a group exercise that others can then continue, or stop an improvised scene that has reached a point that they are not comfortable with.

Some examples of signs I have used are:

· British Sign Language for “Safety” (SignBSL n.d.)

· British Sign Language for “Centre” (SignBSL n.d.)

· An over-exaggerated traditional stage bow

I have found that the presence of the self-care cue is enough for the students to feel safer exploring topics knowing that they had a way to stop at any point that was not only a common language for all in the space, but one that is actively encouraged and established by the facilitator. As previously discussed, the position of power held by those leading an actor training environment can prevent actors from exercising their agency. By not only saying “you can step out at any time” but providing them a way to do so, I have noticed that students lean into exercises more and engage deeper.

My engagement with Trauma-informed Pedagogy informs my aim to “design in opportunities for choice and exercise of agency so students can develop confidence and competence” (Bastian 2024). However, we must still acknowledge the “unavoidable dynamic” (Symonds 2021) between student and teacher. Within this power asymmetry (Villarreal 2021), “no” can be a difficult thing to navigate, and “saying no at the appropriate moment is a skill that many […] need to learn by their experience” (O Hinton, Jr, et al. 2020). Ensuring that students have the opportunity to “[practice] using the self-care cue, [so they feel] able to use this tool when needed” (Villareal 2023) is crucial in empowering them to advocate for themselves.

To consolidate my findings, I have noticed the presence of choice, trust and control may feel unusual to students in a Higher Education setting based on their previous educational experiences, but this doesn’t mean they can’t become more familiar. By providing clear mechanisms for students to exercise agency and consent, they have a means to communicate that may have previously not existed. With these mechanisms, students can begin to feel safer within the actor training environment, which can in turn lead to a deeper engagement with the practice being approached. These tools can improve accessibility, decrease intimidation and make the training environment more enjoyable.

Footnotes and references available in the PDF version of this article