2022 Intimacy Professionals Census Review: Identifying Growing Pains in a Rapidly Expanding Field

by Acacia DëQueer and Kristina Valentine

with contributions from Chelsey Morgan, Lex Devlin, and Ana Bachrach

Introduction

The Intimacy Professionals community is a young but rapidly expanding industry (Villarreal 2022, 5-23). In order to properly chronicle the development of this community as well as plan for how to support the current and future populations of intimacy professionals, we—Acacia DëQueer, Kristina Valentine, and Mx. Chelsey Morgan—created the Intimacy Professionals Census (IPC). The original purpose of this census was to gain insight into the needs and preferences of intimacy professionals—particularly those in the film and television industry—to assist in organizing a union for the benefit and protection of intimacy professionals in the United States. After we closed the census, it became clear that the information we gathered had even broader and more important implications. We felt that it was important to share this information so that intimacy professionals can be better supported in creating a diverse, ethical, and long-lasting industry. The results provide insight into the United States population of intimacy professionals, including the population’s demographic composition, educational background, frequency of work, and the challenges faced in our new industry. We took stock of who is part of the intimacy professionals’ community, who is not, and how organizations can support both as the industry continues to grow.

What information are we analyzing in this paper?

In this paper, we will be presenting the information gathered in the Intimacy Professionals Census in January of 2022. The IPC had 5 sections:

1) Intro,

2) Demographic Information,

3) Further Context,

4) Intimacy Coordinator Census, and

5) Union Planning.

This paper primarily focuses on the information gained from Section 2 and Section 4 of the IPC. Section 1 included identifying information, which has been redacted for privacy reasons. Section 3 consisted of a qualifying question: “Have you worked as an intimacy coordinator, intimacy director, intimacy choreographer, or other intimacy professional (for media production)?” Those who answered “no” were excluded from the results for this paper. Section 5 primarily pertained to unionization and was largely not explored in the analysis of this paper.

It should also be noted that there were 8 respondents from outside the United States (Canada, Malta, the EU, and Australia) that were also excluded from this paper to understand the demographic composition of the intimacy professional’s community more accurately in the United States specifically. We felt that the IPC was not properly advertised internationally and did not garner enough responses to accurately represent the international population of intimacy professionals which also informed our decision to exclude these respondents.[i] For these reasons, we felt it a more accurate representation to exclude respondents outside the USA to compare our findings to the overall population based in the United States.[ii]

Questions

“What is your location or the location you most often work? (City/State, Country)What is your gender identity?What is your racial identity?What is your sexual orientation?Do you identify as disabled? If yes, which identities do you hold?What languages do you primarily speak?Please list any other identities that inform your work as an intimacy professional. (Survivor, Educator, Other S-x Professional, etc.)[iii]Have you worked as an intimacy coordinator, intimacy director, intimacy choreographer, or other intimacy professional (for media production)?Have you received training specific to being an intimacy professional?If you answered “Yes” to receiving training, which organization(s) provided the training?What do you think qualifies an intimacy professional?How often do you work?How do you usually find work as an intimacy professional?In what areas do you work?Do you specialize in any specific genres? (i.e., comedy, musicals, horror, etc.)Do you identify as having a niche/specialization within the field? (i.e.: Extended Intimacy, Racial Intensity, Sexual Violence, Working with Minors, etc.)What barriers do you feel exist for intimacy professionals?Are you or would you be interested in joining a union should one form for intimacy professionals?”

Because the IPC was not designed with analytical analysis in mind, and instead was designed to include as much detail and nuance as possible, we opted to leave almost all questions open-ended. The responses we received to these questions were diverse, intersectional, and varied (Crenshaw 2017). In the process of compiling the results into the following graphs and statistical information, some of this nuance was lost. To the best of our abilities, we have attempted to demonstrate the intersectional nature of the data, but there are many cases where information was simplified. It is our goal to represent the respondents as accurately as possible; however, there are several instances where the language does not reflect that used by the respondents. This shift in language is in service of looking at overall trends and demographic information. Discrepancies will be noted when appropriate.

For this paper, we primarily divided the information into four overarching themes:

1) Demographic Information,

2) Education,

3) Qualification,

4) Job Frequency, and

5) Barriers To Work.

The rest of the “Findings” section of this paper will be dedicated to the reporting of these five areas.

Findings

Demographic Information

Location. Intimacy professionals reported working on the stolen land of the Mvskoke (Muscogee), Pawtucket, Massa-adchu-es-et (Massachusett), Naumkeag, Kiikaapoi (Kickapoo), Peoria, Kaskaskia, Bodwéwadmi (Potawatomi), Myaamia, Cheyenne, Núu-agha-tʉvʉ-pʉ̱ (Ute), Shawandasse Tula (Shawanwaki/Shawnee), Nacotchtank (Anacostan), Piscataway, Monacan, Occaneechi, Karankawa, Coahuiltecan, Atakapa-Ishak, Sana, Munsee Lenape, Wappinger, Schaghticoke, Canarsie, Lekawe (Rockaway), Matinecock, Anishinabewaki ᐊᓂᔑᓈᐯᐗᑭ, Odawa, Meškwahki·aša·hina (Fox), oθaakiiwaki‧hina‧ki (Sauk), Mississauga, Očhéthi Šakówiŋ, Menominee, Wahpekute, 𐓏𐒰𐓓𐒰𐓓𐒷 𐒼𐓂𐓊𐒻 𐓆𐒻𐒿𐒷 𐓀𐒰^𐓓𐒰^(Osage), [Gáuigú (Kiowa), Wichita, Nʉmʉnʉʉ (Comanche), O'odham Jeweḍ, Akimel O'odham (Upper Pima), Hohokam, Cowlitz, Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde, Clackamas, Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians, Lumbee, Skaruhreh/Tuscarora (North Carolina), Cheraw, Shakori, Wašišiw Ɂítdeʔ (Washoe), Powhatan, Eastern Shoshone, Goshute, Nisenan, Miwkoʔ Waaliʔ, Pueblos, Coast Salish, Stillaguamish, Duwamish, Muckleshoot, Suquamish, Manahoac, Seminole, Tocobaga, Calusa, Tohono O'odham, Sobaipuri, Washtáge Moⁿzháⁿ (Kaw / Kansa), Pâri (Pawnee), Syilx tmixʷ (Okanagan), ščəl'ámxəxʷ (Chelan), Yakama, Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation, Kiikaapoi (Kickapoo), and Hoocąk (Ho-Chunk) peoples (Native Land Digital 2021). Colonially, these areas are divided up into 24 of the continental United States and the District of Columbia; intimacy professionals reported working throughout the entire West Coast and Southwestern region, as well as in several states along the East Coast and Northern and Southern areas of the United States (Fig. 1). Respondents primarily reported working in cities with high concentrations of intimacy professionals (3 or more intimacy professionals) in larger metropolitan areas including Atlanta, GA (3); Chicago, IL (7); Houston, TX (3); Los Angeles, CA (14); New York City, NY (9); and Washington D.C. (5).[iv]California was the most common location for intimacy professionals’ work, with 15 respondents (24% of the overall respondent rate) working in one or more parts of the state (14 respondents worked in Los Angeles and 1 worked in San Francisco).

Fig. 1: Map of the United States, illustrating the amount of intimacy professionals who reported working in each state

Fig. 2: Demographics of respondents, based upon personal identification

Gender. The respondents represented many different gender identities, including agender, female, genderfluid, genderqueer, male, nonbinary, and transgender. Female was the most common identity listed, with 63% of respondents answering either as “female,” “woman,” or “she/her” when asked “What is your gender identity?”[i] Nonbinary was the second most common answer, with 16% using the term to describe themselves, often in conjunction with other identities. Of the 63 respondents, 8 (13%) used two or more gender identities to describe themselves (such as nonbinary and genderqueer). Genderqueer and male-identifying presented an equal percentage of respondents—almost 10% each. Agender, genderfluid, and transgender identities each comprised less than 10% of the population. Because agender, genderfluid, genderqueer, nonbinary, and transgender respondents face similar challenges and types of discrimination, they are combined throughout this paper and labeled as “Transgender” (Stonewall 2019). With 30% of respondents categorized as transgender (Fig. 2), the overall intimacy professionals community presented a significantly higher than average population of transgender individuals than the general US population (Meerwijk and Sevelius 2017). In comparison, men were significantly underrepresented, with only 10% of respondents identifying as male.

Sexuality. Intimacy professionals represented a wide range of sexualities as well, with asexuality, bisexuality, demisexuality, homosexuality, heterosexuality, pansexuality, and queerness all represented. While most respondents only used one sexuality to describe their orientation when asked “What is your sexual orientation,” 16% used more than one label (such as queer and bisexual).[ii] For this reason, Appendix A presents this data, highlighting how many respondents identified with each sexuality, instead of counting them in only one category or combining categories. Overall, 68% of respondents were LGBTQIA+ (Fig. 2), which is over nineteen times higher than the national average of 3.5% (Gates 2011). Interestingly, when asked “Do you identify as having a niche/specialization within the field,” only 25% said they specialized in some form of LGBTQIA+ intimacy. Of the different LGBTQIA+ identities represented, the majority—around 30% of respondents—were queer. Heterosexual respondents made up 24% of overall respondents. 8% of respondents chose not to answer.

Race. Although nine different races/ethnicities were indicated in responses, 79% of respondents listed “white” as at least one of their races when asked “What is your racial identity”. This was slightly higher than the national average of 76% (U.S. Census 2021).[iii] Global Majority representation made up 27% of the overall responses from intimacy professionals (Fig. 2), compared to the 39% of the United States population they represented (“U.S. Census Bureau Quickfacts” n.d.). Black representation was just under 10% (Fig. 2), compared to the overall United States population of 13% (“U.S. Census Bureau Quickfacts” n.d.). Filipino representation was surprisingly high at 8%, but was the only Asian ethnicity represented among all respondents. This means that Asian representation was the most under-represented racial demographic compared to the United States population of 5.9% who identified solely as Asian (U.S. Census Bureau Quickfacts n.d.). Jewish made up 6% of the overall respondent rate. Of the 63 respondents, 11 (17%) identified two or more racial identities, which is much higher than the national average of 2.8% identified by the U.S. Census Bureau in 2021: three out of four respondents who identified as Jewish also identified as white (without listing any other racial identities), and Latine/LatinX/Mexican respondents made up 11% of multiracial respondents, with 5 out of 7 Latine/LatinX/Mexican respondents listing more than one race. Hawaiian, Irish, Middle Eastern, and Native (Pamunkey/Tsalagi) each only had one respondent. These 11 respondents were listed as multiracial in Appendix A, but it is important to note none of the respondents used the term “multiracial” to identify. The term “multiracial” was assigned to simplify our analysis. Of the 11 respondents listed as multiracial, 3 of them used the term “mixed” to identify. The rest simply identified 2 or more races in their response but did not assign a singular term. It is also worth noting that while we only asked about race in the IPC, respondents overwhelmingly responded with ethnicities. Throughout the analysis in the rest of the paper, respondents were divided into two racial categories: Global Majority and Non-Global Majority. Non-Global Majority comprised respondents who solely identified as White and/or Jewish. Everyone else was sorted into Global Majority.

Dis/ability. When asked “Do you identify as disabled? If yes, which identities do you hold?” the majority (57%) of respondents answered “no” (labeled as “Abled” in Fig. 2). 16% of respondents answered “yes,” most of which identified physical and/or mental symptoms and/or diagnosis. In comparison, only 8.7% were identified as disabled in the 2021 U.S. Census. 13% of respondents identified physical and/or mental symptoms and/or diagnosis but failed to answer “yes” or said “no” (listed in Appendix A as Other). 14% failed to answer completely, or said they felt uncomfortable disclosing their dis/ability status. Of those who identified physical and/or mental symptoms and/or diagnosis (which includes respondents in both the "Disabled" and "Other" category in Appendix A), over half mentioned learning disabilities/neurodiversity such as ADHD, autism, or executive functioning disorders. Other symptoms or diagnosis mentioned include sensory issues such as vision impairments, mobility issues, chronic pain, and mental disorders such as depression, anxiety, and PTSD.

Languages. Every respondent said they spoke English as a primary language except for one who chose not to answer. However, because the IPC was written and published solely in English and we are only analyzing the data of respondents from the United States, this was consistent with our expectations. 16% of respondents spoke more than one language, Spanish being the most common at 11% of the overall population (Fig. 2), which is consistent with the 13% of Spanish speakers that makes up the general U.S. population (U.S. Census Bureau Quickfacts n.d.). Other languages spoken included Irish, French, Tagalog, Italian, and Brazilian Portuguese (Appendix A).

Survivors. When asked “Please list any other identities that inform your work as an intimacy professional (Survivor, Educator, Other S-x Professional, etc.),” 23 of the 63 respondents (37%) listed “Survivor” for which the common understanding is a survivor of sexual violence (Fig. 2).[iv] This is high compared to the findings of The National Sexual Violence Prevention Center, which reported that 20% of women in the United States “experienced completed or attempted rape during their lifetime” (Smith et al. 2018). However, considering Global Majority, LGBTQIA+, transgender, and disabled populations all experience higher rates of sexual assault on average it is not surprising that the response rate for “survivor” was higher than those of “women” generally (RAINN 2022; Sexual Violence & Women of Color: A Fact Sheet; Gates 2011). Of the 23 respondents, 22% were Global Majority, 74% were LGBTQIA+, 35% were Transgender, and 30% were Disabled (Appendix A). All these identities represented a disproportionately large percentage of those who answered “survivor” compared to the percentage of the overall respondent rate, which was consistent with our expectations.

Educators. A majority of the respondents (65%) listed “educator” when asked “Please list any other identities that inform your work as an intimacy professional. (Survivor, Educator, Other S-x Professional, etc.)” (Fig. 2). While most of the 41 respondents solely listed “educator,” among those who specified, there were a variety of pedagogical fields named in responses, including: gender and sexuality, sex and relationships, consent, sexual assault, movement, and trauma (Appendix A). 17% of respondents listed as an educator reported teaching content relating to relationships and/or sexuality.

Industry. Respondents reported working in a variety of arts industries including circus, dance, film and television (both independent and studio), live performance, opera, and theater (Appendix A). Of all the respondents, 19% worked solely in theater, and 13% worked solely in film/television, while only 1 respondent each reported working in dance or opera exclusively. Because IPC respondents were asked to distinguish between working in independent television/film and in a studio setting, we were able to determine that respondents in this industry were almost two and a half times more likely to work exclusively in independent film/television as opposed to those who worked in both a studio setting and on independent productions. While many respondents specialized in an individual industry, the majority worked in more than one industry. Intimacy professionals who worked in two industries—typically film/television and theater—comprised 38% of all respondents and those who worked in three or more industries comprised 27% of all respondents (Fig. 2). Most respondents who worked in industries such as dance, circus, and opera worked in two or more industries.

Education

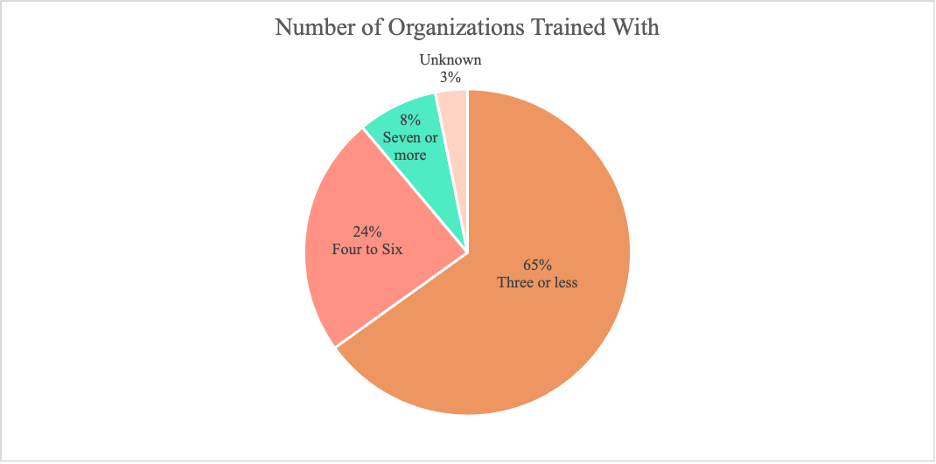

Participants’ responses emphasized that education was important to intimacy professionals. When asked “Have you received training specific to being an intimacy professional?” every respondent answered yes. When prompted to elaborate on which organizations respondents trained with, a wide variety were mentioned including: Centaury Co, Heartland Intimacy Design, Humble Warrior Movement Arts, Intimacy Coordinators Alliance for Film and Television (ICAFT), Intimacy Coordinators of Color (ICOC), Intimacy Directors and Coordinators and/or Intimacy Directors International (IDC/IDI), Intimacy for Stage and Screen, Intimacy On Set, Intimacy Professionals Association (IPA), Moving Body Arts, The National Society of Intimacy Professionals (NSIP), and Theatrical Intimacy Education (TIE) (Appendix B). Respondents also reported receiving additional training such as Mental Health First Aid (MHFA), private mentorship, or unspecified intimacy training. TIE and IDC were by far the most attended training organizations; 78% of respondents trained with TIE and 73% of respondents trained with IDC. These organizations seem to serve the purpose of major bases of knowledge for intimacy professionals, as the majority (84%) of professionals who trained with two or less organizations trained with TIE and/or IDC; the only other organization that any respondents trained with exclusively was Centaury Co. IDC/IDI and TIE remained popular no matter how many organizations individuals trained with. 40% of respondents reported training with ICOC, making it the third most popular training organization. Most other organizations seemingly served as supplementary training or simply one of multiple organizations respondents trained with. Most of the respondents (65%) reported training with 3 or less organizations (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3: Pie chart indicating the amount of organizations intimacy professionals worked with in pursuit of training

Qualification

Because the answers to the question “What do you think qualifies an intimacy professional?” were open-ended, to better be able to analyze the data, we chose to identify common themes. Appendix C contains all the themes we identified and the number of respondents that mentioned each theme as a necessary qualification for intimacy professionals.

General Training. The “General Training” category included responses that referred to training/classes without specifying subjects or training programs. General Training was the most commonly identified qualification, with 54% of respondents including it as a necessary qualification for intimacy professionals. These responses seem to assume a shared knowledge with us as to what “training” could look like, without specifying further.

Experience. The second most frequently cited qualifier was “Experience,” which included responses that stated prior experience in the arts and entertainment industry as a necessary qualification. 41% of respondents mentioned experience as a qualification. Respondents indicated that working in the arts and entertainment industry in a different role before transitioning to intimacy professionals’ work seemed to be helpful, because it familiarized the professional with the etiquette, power imbalances, chain-of-command, and best practices used in their industry.

General Diversity/DEI. The “General Diversity/DEI'' category included responses that mentioned prioritizing Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) or Justice, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion (JEDI) education and/or lived experience or speaking to a desire/education around facilitating diversity, but which did not specifically mention anti-racism or LGBTQIA+ education. 38% of responses generally mentioned an understanding or study of diversity or DEI training as something that would contribute to the background of a qualified intimacy professional but did not specify further. In addition to the “General Diversity/DEI” category, we also created the “Anti-racism” category and an “LGBTQIA+” category. The “Anti-racism” category included responses that specifically mentioned the need for anti-racism education or an understanding of anti-racist principles and best practices. 37% of respondents highlight anti-racism as a specific focus. The “LGBTQIA+” category included responses that specifically highlight an education/understanding needed to support LGBTQIA individuals. 17% of respondents mentioned the need for LGBTQIA+ education.

General Mental Health. The “General Mental Health” category included responses mentioning training or developed understanding of mental health. On top of the “General Mental Health” category, a category labeled “MHFA'' was created to depict responses that mentioned Mental Health First Aid (MHFA) specifically. MHFA is a specific training and certification offered by The National Council for Mental Wellbeing. MHFA teaches individuals how to respond to mental health emergencies—such as panic attacks, overdose, or suicidal thoughts—and trains students in providing resources for receiving ongoing care (Mental Health First Aid USA 2022). Although intimacy professionals are not mental health professionals, they are expected to take care of the psychological safety of actors as well as their physical safety (DëQueer 2022). 24% of responses highlighted the need for general mental health education/understanding with 16% specifically mentioned MHFA Certification. There seems to be a general understanding that intimacy work can trigger emotional responses, that actors with mental health challenges have specific needs and barriers, and that an intimacy professional should have the tools to understand and navigate that vulnerability.

Communication. The “Communication” category included responses that highlighted the importance of training/skills in the areas of conflict resolution and communication. 33% of respondents mentioned the need for the development of communication skills such as de-escalation, negotiation, conflict resolution, tactful language for difficult topics, or the ability to navigate power dynamics. One summarized this thought by writing: “An intimacy professional can have all kinds of specialties and backgrounds, but they need to be excellent communicators and collaborators who can stay grounded and navigate the complexities and nuances of challenging situations where emotions/stakes often run high.” We were able to identify a common theme that intimacy professionals strive to cultivate the ability to navigate high-stress situations and advocate for others with sensitivity.

Movement. The “Movement” category included responses that mentioned movement or choreography training and/or experience. Intimacy work is clearly a physically based craft, as we are assisting in storytelling conducted with bodies. 29% of respondents included training or experience with movement or choreography in their answers. There seems to be a vocabulary that is useful to learn to communicate choreography with actors. Take, for instance, the popular The Language of Movement: A Guidebook to Choreutics by Rudolf von Laban, or the techniques established in Chelsea Pace’s Staging Sex, where Pace differentiates levels of touch as skin level, muscle level, or bone level (Pace and Rikard 2020a). Language and techniques created for choreography are used to gain specificity of movement in a professional, desexualized method (Barclay 2022).

Consent. The category of “Consent” included responses emphasizing education specific to consent and how to practice consent. Consent and the communication surrounding its practice was also a high priority, included in 21% of responses. A deep understanding of consent allows intimacy professionals to delve deeper into their work while assuring all members of a production are supported in exercising their bodily autonomy.

Sex Ed. The “Sex Ed” category consists of responses mentioning sexual health education as a necessary qualification. 13% of respondents mentioned sexual health education. Intimacy professionals expressed the need to have an idea of what is attempting to be simulated during intimacy choreography. Intimacy professionals are also responsible for addressing health and safety concerns regarding fluid exchange and barriers between actors (SAG-AFTRA 2022; Valentine 2021). Generally, the argument is that sexual health education can inform health and safety protocols for actors and create more authentic storytelling.

Mentorship. The “Mentorship” category included responses with an emphasis on mentorship, apprenticeship, or shadowing. These responses indicated a belief that an accountability system was present in a mentorship relationship, so that when a new professional begins working, they were doing so with some supervision. Mentorship was the least common qualification response besides certification, with only 3 (5%) respondents mentioning mentorship as a necessary qualification.

Certification. The “Certification” category consisted of responses that specifically stated official certification as is currently available in the field as a necessary qualification for an intimacy professional. A handful of organizations offer certifications for intimacy professionals; interestingly, based on our data, certification from any of these organizations is not widely viewed as necessary or qualifying, as only one respondent included certification in their response.

Because the responses were open-ended rather than multiple choice, it is possible that when presented with any of the subjects we are discussing, someone who did not think to or did not have time to mention something in a free response may still have selected it if presented as a multiple-choice option. For example, we noticed that just one response specifically mentioned disability education or experience. We are not concluding that the intimacy professional community would disagree that disability education could or should be something that could be an aspect of someone’s training, but it is interesting to note that this aspect of diversity unfortunately does not seem to be at the forefront of our minds at this time.

Fig. 4: Qualifying categories represented by number of mentions

Job Frequency

Job Frequency (data presented in Appendix D) was used as a metric for the level of involvement in the broader arts and entertainment industry as an intimacy professional, with those working on more than one project per month being considered more involved, those working on less than one project per month being less involved, and those working on approximately one project a month falling in between. Job frequency was then cross referenced with the demographic information that was collected, to get a picture of what qualities and characteristics tended to lend themselves to greater involvement within the field. The distribution of job frequency among respondents demonstrates that the majority of respondents (32, making up 51% of all respondents) work on less than one project per month; 17 respondents (27%) work on approximately one project per month; and only 14 (22%) work on more than one project per month (Fig. 5). Job frequency was then cross-referenced with other collected demographic information including gender, sexuality, race, dis/ability, educator status, sexual assault survivor status, number of organizations trained with, and industries worked in.

Fig. 5: Job frequency distribution across the population of respondents.

Gender. Job Frequency was fairly evenly distributed among genders, with men being slightly more likely to work more than one job per month. 33% of the male respondents worked on more than one project per month, while only 23% of the female respondents and 18% of the transgender respondents worked on more than one project per month.

Sexuality. Job Frequency distribution indicated that people who were LGBTQIA+ were more likely to work on multiple projects per month. 26% of the LGBTQIA+ respondents worked on more than one project per month, while only 20% of straight respondents worked on more than one project per month. Even when looking at those that worked on at least one project per month (including both the people who worked approximately one project and those that worked more than one project per month), 56% of the LGBTQIA+ respondents worked on at least one project per month while only 40% of the straight respondents worked on at least one project monthly.

Race. When looking at the distribution of race, there was not much of a difference in high job frequency between the Global Majority and Non-Global Majority respondents, with 24% of the Global Majority respondents and 22% of the Non-Global Majority respondents working on more than one project a month. However, when looking at low job frequency, 41% of the Global Majority respondents worked on less than one project a month while 54% of the Non-Global Majority worked on less than one project a month.

Dis/ability. Disability seemingly had a large negative impact on job frequency, with only 1 (10%) of the disabled respondents working on more than one project monthly, whereas 7 (19%) of the currently abled respondents worked on more than one project per month. 70% of disabled respondents worked on less than one project per month, while only 53% of the currently abled respondents worked on less than one project per month. In addition, when the respondents who responded “yes” to being disabled were combined with those that fell into the “Other” category, (those that didn’t respond “yes” but rather listed physical and or mental symptoms and or diagnosis) 33% of the respondents in those two categories worked on more than one project per month - a greater percentage than their currently abled counterparts.

Survivor. When sexual assault survivors were cross-referenced with job frequency, the data indicated that being a survivor had a positive relational impact, with 26% of the respondents who said they were survivors working on more than one project per month, while only 20% of respondents that did not report that they were a survivor worked on more than one project a month.

Educator. Arguably, the most striking information learned was the correlation between being an educator and frequency of work. Of the 14 respondents who said they worked on multiple projects per month, all of them said they were educators.

Industry. Job frequency was looked at across industries. It was quickly obvious that respondents who worked in at least three industries were significantly more likely to work on multiple projects per month. 47% of the respondents that reported working in at least three different industries worked on more than one project a month whereas only 13% of respondents that reported working in one or two industries worked on more than one project a month. Even just working in two different industries decreased the likelihood of working on more than one project a month to be about equivalent to those that worked in only one industry. 13% of the respondents who worked in two industries and 14% of the respondents who worked in only one industry worked on more than one project a month.

Number of Training Organizations. Comparing job frequency among respondents who trained with three or less intimacy organizations to the job frequency of those who trained with four or more organizations, our data indicated that training with three or less organizations actually had a positive impact on job frequency. 24% of the respondents who trained with three or less organizations worked on more than one project per month, and only 15% of the respondents that trained with four or more organizations worked on more than one project per month. However, when these respondents were compared to those that trained with seven or more organizations, those that trained with seven or more organizations were more likely to work on more than one project per month with 60% of those that trained with seven or more organizations working on more than one project per month.

Overall, the factors that tended to yield higher work frequency—and therefore greater involvement in the field—were working as an educator, working in at least three different industries as an intimacy professional, and training with 7 or more organizations.

Barriers

Respondents were asked to identify what barriers they felt existed for intimacy professionals in an open answer section of the IPC. Because the answers to the question “What barriers do you feel exist for intimacy professionals?” were open-ended, we chose to identify common themes to better be able to analyze the data. Our sorting was subjective, therefore all quantities come with a reasonable margin of error. Additionally, because we asked, “What barriers do you feel exist for intimacy professionals?” instead of, for example, “What barriers have you encountered personally as an IP?” it is impossible to determine how people’s identities truly intersect with the barriers cited. We cannot know whether the barriers respondents cited were ones personally encountered, or a projection of the barriers individuals perceived within the broader intimacy professionals community. Despite this, we have chosen to analyze barriers cited against several other data points including demographics, education, and job frequency to better understand and support community members.

Undervalued/Misunderstood. Feeling “Undervalued/Misunderstood” by the industry at large was the most commonly mentioned barrier, with 41% of respondents identifying difficulty working with the broader arts and entertainment industry (Appendix E). More specifically, convincing directors and producers of the value of an intimacy professional seemed to be a common challenge. This had a direct impact on respondents’ ability to be paid appropriately for their work and receive the appropriate space and time to run rehearsals for scenes of intimacy. Respondents also mentioned that in some instances, misinformation about what intimacy professionals do negatively impacted their ability to work, such as being perceived as the “fun police” or a safety monitor, instead of an artistic collaborator. Overall, there were no significant trends for this category when cross-referenced with other information. However, there was a common connection between underqualified intimacy professionals and respondents feeling intimacy professionals were misunderstood or undervalued. Of the 4 people who cited underqualified intimacy professionals as a barrier, three of them connected the problem to contributing to the misinformation in the broader arts and entertainment community. 6 people also connected a lack of cohesion or backing in the intimacy professionals community as contributing to feeling misunderstood or undervalued in the broader industry because there are currently very few to no regulations for training, rates, or terminology; nor is there a union to organize such issues. Across the board, a lack of understanding in the broader arts and entertainment industries presented the largest challenge to respondents.

Gatekeeping. The second most commonly cited barrier was “Gatekeeping,” with 30% of respondents identifying power dynamics within the industry limiting work and community involvement (Appendix E). This was an interesting datapoint speaking to the group’s perceptions of a sense of isolation from the larger intimacy professionals community. Some respondents connected their perception of gatekeeping to their other criticisms, such as viewing the difficulty of finding willing mentors as a means of gatekeeping. In general, gatekeeping was strongly associated with comments about qualifications, certification, cost of training, and freedom of information. It also seems that because there is not a singular organizational body, training institution, or union that represents intimacy professionals as a whole (as identified by the 13 responses categorized by Cohesion/Backing), the social power of those perceived to be more experienced was amplified. Nepotism, or hiring/suggesting hiring friends was cited by several respondents as a barrier, which was supported by the fact that 95% of intimacy professionals reported networking as one of the main means by which they found jobs. Several people wrote about lack of connections in the entertainment industry or lack of an agent as presenting a barrier to finding and getting work. Racial homogeneity among those intimacy professionals who were perceived as having more power, visibility, or experience was also a frequent complaint when discussing gatekeeping, with multiple respondents feeling the need to receive approval from their white peers to pursue work in the field. Half of all Global Majority respondents identified gatekeeping as a barrier in the industry. In comparison, only 22% of Non-Global Majority respondents identified gatekeeping as a barrier. “Gatekeeping” was a commonly occurring word in responses to the IPC, with some answers submitted being “Gatekeeping” and nothing else. However, in responses where respondents elaborated on their perception of gatekeeping, their language was deeply emotional, using words such as “horde,” “impossible,” “antiquated,” “dictate,” “territorial,” “elitism,” “monopolizing,” “exclusiveness,” “protectiveness,” and “evasive.” Overall, those who cited gatekeeping had negative associations about the intimacy professionals community and feelings of being excluded, sometimes intentionally, by those they perceived as having more visibility or power.

Cost of Training. “Cost of Training” was cited as a barrier by 29% of respondents (Appendix E). LGBTQIA+ respondents were more likely to report financial barriers, making up 78% of respondents who cited cost of training. Disabled respondents were also disproportionately impacted, making up 22% of respondents who cited cost of training as a barrier. Respondents working exclusively in theater also struggled to pay for training, making up 39% of respondents who cited a financial barrier compared to the 19% of the overall respondent rate they made up. Of the 18 people who cited financial barriers, 8 also identified certification as a barrier, with many connecting the high cost of certification programs to difficulty entering or receiving recognition in the field. This was often connected to arguments about gatekeeping and a general preference for qualifications such as previous work experience over certification.

Certification. Overall, 24% of respondents identified “Certification” as a barrier in the industry (Appendix E).[i] It is worth noting that when asked “What do you think qualifies an Intimacy Professional,” just one person listed certification, as opposed to the 15 responses mentioning certification as a barrier in the industry. In the received responses, discussion surrounding certification was closely tied with sentiments around gatekeeping. Multiple comments were made about the connection between the SAG•AFTRA Intimacy Coordinator Registry, certification, gatekeeping, and cost of training. The cost of training from SAG•AFTRA accredited training programs currently ranges from $5000 to $15,000, according to those programs that listed their prices online (Intimacy Directors and Coordinators 2020; Centaury Co.). Many of the programs on the list of SAG•AFTRA Accredited Intimacy Coordinator Training Programs do not clearly communicate the price of “certification” or the means of signing up for their training. The link for the Intimacy Coordinators Education Collective on the SAG•AFTRA accredited training programs website, for example, simply directs the user to an email address (SAG•AFTRA). Even Centaury Co., which advertises that their “mission is to diversify the field by training historically excluded individuals to become Intimacy Coordinators for Film & Television” with small class sizes aimed at Black, Indigenous, POC, and LGBTQ++ individuals, costs $5,000—not including supplies, transportation, and logging for trainings—without any scholarships offered for trainees from low-socioeconomic communities (Centaury Co.).

It is important to understand the risk involved when one takes on the cost of such training, especially considering that finding work in the field is not guaranteed, as illustrated in the Job Frequency section of this article. This risk to cost ratio can be a large barrier to entry, disincentivizing individuals considering entering the intimacy professionals field. It might also contribute to an individual's ability to continue working in the field, as they may need to work a different job to support themselves and pay for “certification.” This is a large barrier to continued work. IPA’s “information packet” for their Intimacy Coordinator Training Program states that “most IC’s work a schedule that would be considered part-time… due to the fact that this job is a freelance position and the hours that film/TV industry employees work are highly variable,” continuing on to say “it would be very challenging to balance doing this work with another job that has a fixed schedule (such as seeing clients on a regular schedule)” (Intimacy Professionals Association 2022). For those without sufficient financial cushioning, the cost of training followed by a lack of return on their investment makes staying in the field difficult, leaving some intimacy coordinators to make the devastating choice to leave the industry after already investing in their training.

The SAG•AFTRA Intimacy Coordinator Registry does not explicitly require certification. However, the SAG•AFTRA Intimacy Coordinator Accreditation Program registry prioritizes certification programs. Some of the requirements named in the Standards and Protocols for the Use of Intimacy Coordinators document (2020)—such as “Movement coaching and masking techniques” and “Understanding of Guild and Union Contracts that affect nudity and simulated sex”—can be difficult to find and/or prove outside of certification programs, making working on union productions more difficult. As mentioned in the section on gatekeeping, race and the racial composition of those running certification programs was seen as a barrier to certification. In some cases, the lack of racial diversity within the leadership of certification programs discredited certification programs and their “authority” in the field altogether. While race was an issue when discussing certification, the racial distribution of respondents who identified certification as a barrier was consistent with the overall racial distribution of IPC respondents.

Mentorship. While “Mentorship” was not cited as frequently, with only 11% of respondents mentioning it as a barrier, mentorship connected with several other topics such as gatekeeping, cost of training, certification, underqualified intimacy professionals, and finding work. Interestingly, several people expressed difficulty not only in finding a mentor, but in finding a qualified mentor. COVID, a lack of information on how to find a mentor, finances, and the fact that there are more people interested in becoming intimacy professionals than there are professionals to mentor all presented barriers to mentorship. Of those who identified mentorship as a barrier, all of them studied with 3 or fewer organizations. 71% of respondents who identified mentorship as a barrier trained through IDC/IDI and 57% through TIE. Other organizations respondents trained through included ICOC, Centaury Co., and NSIP. However, these three organizations made up a significantly smaller percentage of those organizations individuals trained through who identified mentorship as a barrier. Considering 43% of those who said mentorship was a barrier also identified financial barriers we can conclude there are contributing factors to the number of organizations trained with other than interest/desire in further training and that given the opportunity individuals would pursue further mentorship or educational opportunities.

Cohesion/Backing. 21% of respondents spoke to what we have identified and labeled as “Cohesion/Backing” in the analysis of the IPC and this paper (Appendix F). These responses commented on the lack of a singular organizational body to regulate, advocate for, and speak on the behalf of the intimacy professionals community. Comments included discussion of unionizing or joining with an existing union such as IATSE or SAG•AFTRA but extended beyond the formation of a singular body or organization to the dangers of isolation as a freelancer. Responses connected to finding work, underqualified intimacy professionals, and certification. A frequent concern was how a lack of regulations lead to unqualified intimacy professionals working in the field. It wasn’t just a lack of awareness with intimacy professionals themselves, but also a lack of knowledge on the part of hiring productions or institutions as to the qualification requirements for an intimacy professional. Respondents also mentioned a discrepancy among certification programs’ standards of knowledge and certification requirements.[ii] There was also a desire for consistency in other areas, such as rates, so that productions could accurately budget for intimacy professionals. Many of the answers relayed a desire for clearer communication and understanding with productions about the needs of intimacy professionals. Respondents also expressed a desire for stronger regulations from unions such as SAG•AFTRA in requiring intimacy professionals for scenes of intimacy to help with job creation. Of those respondents who were categorized as wanting more cohesion/backing, 31% reported working exclusively in the film/television industry, and 46% reported training with 4 or more organizations. Lack of cohesion or backing was also more likely to be felt by respondents who worked on approximately one project a month or more (69%) meaning people working frequently in the film and/or television industry were more likely to be concerned with this issue.

Finding Work. Of the 19% of respondents who identified “Finding Work” as a barrier, most expressed confusion in locating jobs or connecting with employers. A lack of knowledge seemed to be the biggest barrier, but the absence of a central place to find jobs or for productions to find and hire intimacy professionals was a large contributing factor. Again, the SAG•AFTRA intimacy coordinator registry presented a barrier to employment because productions are meant to find “qualified” intimacy coordinators through the list, but intimacy professionals could not join the list without first having worked on several SAG•AFTRA productions (SAG-AFTRA 2020; 2022). This gap was indicated by the fact that so many respondents worked on independent productions instead of studio productions, even though there are no shortage of high-budget SAG•AFTRA productions which could use an intimacy coordinator; productions that received a PG-13 or R rating (which often feature intimacy, nudity, and/or sex) made up 75% of the market (The Numbers 2022). Discussions of gatekeeping were also connected to barriers to finding work and were supported by the fact that networking was the top way to get jobs with 95% of respondents reporting they used networking to “find work as an intimacy professional.” Of those respondents who cited finding work as a barrier, 83% were categorized as LGBTQIA+. Respondents were also significantly more likely to be Global Majority Members with 58% of those citing finding work as a barrier compared to the 27% of the overall population they comprised. Surprisingly, job frequency did not have a large impact on finding work as respondents from all three categories (Less than one project a month, approximately one project a month, and more than one project a month) reporting finding work as a barrier, indicating that regardless of job frequency there was a sense of confusion, lack of knowledge, or gap in communication when finding and coordinating with employers.

Lack of Diversity. “Lack of Diversity'' was cited as a barrier that exists for intimacy professionals by 10% of respondents (Appendix F). While some respondents spoke about a lack of diversity in the stories being told, most focused on a lack of diversity within the intimacy professionals community itself. Lack of diversity was connected to comments about gatekeeping. Visibility within the industry and the face of the intimacy professionals community being limited to a few white female individuals was specifically concerning to respondents. Lack of professional diversity in fields such as sexual education or mental health was also mentioned. Respondents who identified lack of diversity as a barrier worked in a variety of industries but primarily trained with 3 or less organizations. Interestingly, of those respondents who identified lack of diversity as a problem within the industry, almost all were white currently abled women who were members of the LGBTQIA+ community – all identities that were overrepresented in the intimacy professionals community. While these identities mentioned face systemic oppression through their LGBTQIA+ and female identities, our data shows that a majority of intimacy professionals are LGBTQIA+ and female. It follows, then, that the respondents’ sense of isolation and otherness informed their answer, or perhaps their increased awareness of diversity in the workplace through their lived experience.

Underqualified Intimacy Professionals Because we elaborated on respondents’ comments on underqualified intimacy professionals, we will not elaborate on them further, other than to mention that men and non-educators who had trained with 7 or more organizations were disproportionately likely to cite underqualified intimacy professionals as a barrier.

Fig. 6: Frequency of barrier category mentions

Discussion

By evaluating the respondents’ answers from the IPC, we have learned that representation of queer women within the intimacy professionals community was relatively high with 63% identifying as female and 68% being categorized as LGBTQIA+. However, the vast majority of respondents were currently abled and white. While there was a much higher than average representation of gender diversity with agender, genderfluid, genderqueer, nonbinary, and transgender people all being represented, men were drastically underrepresented. It should also be noted that the male respondents were largely homogeneous in areas such as race, disability, and survivor status—most having a closer proximity to power (The National Domestic Violence Hotline 2021). This is not surprising, considering men are often discouraged from the field in subtle ways, as illustrated by a section in IPA’s Intimacy Coordinator Training Program Information Packet that says “We have observed that employers sometimes demonstrate a preference for female IC’s” when discussing whether they accept male applicants (Intimacy Professionals Association 2022). Global Majority members were underrepresented, particularly those of Asian and specifically East Asian descent. Global Majority members were also more likely to cite finding work as a barrier in the industry. The lack of racial diversity amongst intimacy professionals remains a problem, despite efforts to offer scholarships and training opportunities specifically for Global Majority individuals interested in becoming intimacy professionals (IDC Professionals 2019; Theatrical Intimacy Education 2020).

Regarding representation of disabled intimacy professionals, respondents who were deaf or hard of hearing were noticeably missing. While people who are deaf or hard of hearing should not necessarily be listed as disabled, it is important to note that none of the respondents listed ASL when asked “What languages do you primarily speak,” which means there might be no intimacy professionals available to support deaf or hard of hearing actors (Jones 2002). In a time where Deaf representation is on the rise, as exemplified by the Academy Award Best Picture Winner CODA (2021), Marvel’s Eternals (2021) and Hawkeye(2021), Deaf West Theater’s Spring Awakening, and Hulu’s Only Murders In the Building (2021-), it is necessary that we work towards providing specific support to deaf actors because the strategies for communicating boundaries, consent, choreography, etc. will necessarily change based on the means of language or communication. To properly support the development of deaf and hard of hearing intimacy professionals, it is likely that educational institutions such as IDC and TIE will need to evaluate accessibility needs and hire interpreters. Also underrepresented amongst those who identified as disabled were individuals using mobility aids. This, too, may affect the work and choreography of an intimacy professional, as their lived experiences can provide valuable insight for storytelling. Because most organizations provide training virtually (Intimacy Directors and Coordinators 2022; Theatrical Intimacy Education 2022), it is unclear what accommodations might make this work more accessible for those who use mobility aids.

Another notable finding from our analysis of demographic information was the high rate of sexual assault survivors, many of which were LGBTQIA+, Global Majority members, and Disabled. Considering that these populations are more likely to be depicted as victims of sexual violence in the media as well, the need for education not only for choreographing scenes of sexual violence safely for actors, but also for the intimacy professionals themselves, becomes apparent. Trauma stewardship is important when training individuals to enter the field (The National Society of Intimacy Professionals & Moores 2021); classes aimed at diversifying the field, in particular, should consider how topics of sexual violence might impact participants.

Our findings discovered that the majority (65%) of respondents were educators in areas relating to—but not directly encompassing—staged intimacy, such as gender and sexuality, sex and relationships, consent, or movement. On top of that, there was a correlation between frequency of work and being an educator as every respondent who worked on more than one project per month was an educator.[i]

We also learned that every respondent had received some sort of education specific to being an intimacy professional. Most people trained with 3 or less intimacy organizations. Of the organizations listed, IDC, TIE, and ICOC were the most popular. However, those who cited mentorship as a barrier to the industry were more likely to train with one or more of these three organizations exclusively as opposed to training with additional organizations such as Heartland Intimacy Design, NSIP, Humble Warrior Movement Arts, or Intimacy for Stage and Screen.

Certification was mentioned in both qualifications and barriers by respondents. However, only one respondent mentioned certification as a qualification for intimacy professionals as opposed to the 15 respondents that mentioned certification as a barrier indicating that certification was not viewed as necessary to work in the field and that it was generally unpopular among respondents for a variety of reasons. Many people also cited cost of training as a barrier to the industry, with 29% of respondents mentioning it, many in connection with certification.

When asked “What do you think qualifies an intimacy professional,” respondents mentioned a variety of areas, including general mental health, general (intimacy specific) training, MHFA certification, movement, communication, general diversity/DEI, anti-racism, LGBTQIA+, industry experience, sex ed, and consent. As the intimacy professionals community grows, we recommend these in addition to disability education, serve as a general list of qualifications for which any applicant must meet when being considered to serve as an intimacy professional on a production.

Respondents reported working in a variety of arts industries including circus, dance, film and television (both independent and studio), live performance, opera, and theater. Those who reported working in at least three different industries were significantly more likely to work on more than one project a month. The other largest factor correlated with higher work frequency besides working as an educator or working in three or more industries was training with 7 or more intimacy organizations.

Of the barriers cited, feeling undervalued or misunderstood by the arts and entertainment community, encountering exclusionary gatekeeping practices within the intimacy professionals community, the high cost of training, the perceived need for certification, and a lack of cohesion within the intimacy professionals community as well as backing from the arts and entertainment industry were the most pervasive.

Feeling undervalued/misunderstood by the arts and entertainment industry at large was the most commonly cited barrier to the industry. The good thing about this being the largest barrier is that misinformation and a lack of understanding can be corrected with help from unions, educational institutions, publishers, and other large organizations if they are properly informed about the duties and qualifications of intimacy professionals as well as the myriad of benefits they bring to a production. While efforts to educate the broader community such as the SAG•AFTRA Intimacy Coordinator registry and SAG•AFTRA Intimacy Coordinator Accreditation Program registry have taken place, because these efforts have been planned and executed behind closed doors and without accountability efforts, they have largely contributed to respondents’ experiences with Gatekeeping which was the second-largest Barrier cited. It was suggested that other support systems such as agents could aid professionals, but there is currently only one agency that we know of which manages intimacy professionals—IPA. This contributed to gatekeeping as well, because individuals interested in being represented by the agency have to be certified through IPA to be eligible. This presents both financial and mentorship barriers, as the program costs $7,000 for certification, plus travel, and there are not enough instructors to train all those interested (Intimacy Professionals Association 2022).

The barriers this paper outlines, particularly those speaking to certification, gatekeeping, and cost of training (such as the SAG•AFTRA accredited certification programs) prove that choosing to become an intimacy professional can be a poor financial investment for those entering the field. This unfortunately leaves the arts and entertainment industries in danger of preventing intimacy work from becoming a sustainable mainstay of the entertainment industry and leaves both individual performers and companies in the same place they were before the #metoo movement provided enough leverage for the position to exist in the first place (Hilton 2020). However, while “Finding Work” was listed as a barrier by intimacy professionals, it primarily was connected to confusion in locating jobs or connecting with employers. Entry into the field, particularly for film and television, can be almost impossible without connections in the industry. As IPA’s Intimacy Coordinator Training Program info packet says, “For many IC’s, how much work they get depends largely on their pre-existing professional network of film industry contacts” (Intimacy Professionals Association 2022). It could be that gaining the support of job recruitment websites for arts and entertainment professionals such as Backstage, Hollylist, or StaffMeUp could greatly aid in the development of the industry by creating options for connecting employers and intimacy professionals, particularly those without a background in film, television, or theater. Currently, the only central location for intimacy professionals to find work is the Facebook group titled “I Need an Intimacy Professional (Coordinator/Director/Consultant),” which hosts an average of just 4 jobs each month for nearly 500 members—most of which offer a daily compensation rate of $0 to $350, which is far below the industry standard for intimacy professionals (Hendon and DëQueer 2021; Pace and Rikard 2020b). Alternatively (or in addition to the former suggestions), a single site dedicated to providing a platform for intimacy professionals to connect with potential employers could greatly benefit the community and decrease confusion for those attempting to find work.

It’s not just a disconnect between employers and intimacy professionals that presents a problem. Rather, it is also a lack of productions, theaters, and other arts organizations thinking to hire intimacy professionals—probably due to the reasons outlined in intimacy professionals feeling Undervalued/Misunderstood. After educating potential employers about the benefits of and reasons for hiring an intimacy professional, other solutions to encourage job production might lie in economic incentives. One solution might be for unions such as SAG•AFTRA to provide financial incentives for productions to hire an intimacy professional to encourage job growth similar to their Diversity-in-Casting Incentive, which increases the total budget maximum for Moderate Low Budget Project Agreements and Low Budget Agreements for ensuring “a minimum of 50% of the total speaking roles and 50% of the total days of employment are cast with performers who are” women, senior performers, performers with disabilities, or people of color (SAG•AFTRA). A financial incentive, unlike a requirement to have an intimacy professional present, encourages productions to hire an intimacy professional while understanding that one might not be available due to the limited number of qualified individuals currently working in the field. Another option would be for training programs to have deferred payment plans, where those seeking to enter the field are given a predetermined time to pay off classes and training. Because intimacy professionals overwhelmingly comprise underrepresented communities, nonprofits and government agencies might also be convinced to create financial assistance programs such as fellowships, grants, or scholarships. An excellent example would be how IPA partnered with the “New Mexico Film Office to provide an opportunity for up to three New Mexico residents to receive a grant that covers 60% of tuition for” their certification program (“Letter to Acacia DëQueer” 2021). Additionally, if governments could be enticed to act, some bodies might be convinced to provide incentives for hiring intimacy professionals in the same way states provide tax incentives for film production (Brainerd and Jimenez 2022).

Financial deterrents are not the only barriers to the industry expanding and retaining intimacy professionals, however. There are emotional and social barriers as well. Gatekeeping in particular was a heavy, emotionally charged term for intimacy professionals. We seem to be asking each other, Do you want me here? Am I good enough? Here, gatekeeping implies ownership of job opportunities, knowledge, community, and more. Factually, though, there are professionals who have been doing intimacy work for stage and screen since before any certifications or accreditations were created. The costume department, for example, provided what we now call “modesty garments” long before intimacy professionals were there to assist them (Dor 2022). The field is so new, too, that the difference between a mentor and mentee can be just a couple of years of experience, given that the field’s origins are tied to the #metoo movement, and most of its growth has occurred in just the last 5 years (Villarreal 2022). Intimacy work, as it is now titled and organized, has not been around long enough for any intimacy professional to have decades of experience over another. Even so, hierarchies and leadership have emerged, creating structure in the absence of regulations or broader authorities such as a union for intimacy professionals. Individuals perceived as leaders within the community seemed to be tasked with validating an intimacy professional’s education and experience, according to our findings. The voices of these perceived leaders have been amplified while individuals who are working but not as visible have been minimized or unheard. This power dynamic is an argument for grassroots organizing efforts to utilize the opinions, experience, and needs of the broader intimacy professionals community.

Conclusion

We are particularly interested in seeing actionable applications of the information presented here. This data can inform the actions of leaders of training organizations and future community organizing/unionization efforts. Other applications can be imagined in the sharing of this information outside of the intimacy professionals community as well, such as communicating our needs to professionals in our industry less familiar with intimacy coordinators, directors, and choreographers. We also seek to create a precedent of seeking and including the opinions and specific needs of individual community members in our work as we continue to experience the growing pains of our exciting young industry.

Fostering a sense of community and inclusivity, instead of exclusivity or gatekeeping, will require continued efforts such as the IPC in order to communicate to every member of our community, we want to know what you think, what you are bringing to this work, and how you would like to shape its future. We would like to emphasize that embodying the values intimacy professionals espouse as an industry of anti-racism, creativity, integrity, sustainability, and ethics must start in our own community (“Core Values” n.d.). Opposing the existing power structures in our industry that result in harm and inequities will take conscious, cooperative work with long-term focus. We hope intimacy professionals will be able to prove to the entertainment industry—by the way we treat each other and those seeking to join us—that we are here to stay, and we are here to make things better.

Endnotes and References available in the PDF version of this article