Asserting Boundaries and Conflict Resolution with A Midsummer Night’s Dream: Consent-Based Practices and Shakespeare

by Matthias Bolon

Power is always present in the room, whether wielded by a director, teacher, or facilitator. Pace’s ideas create a foundation that works in any room and with any group when discussing boundaries or working an intimate scene.

Introduction

The four established relationships in Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night's Dream reveal myriad complexities that can be utilized in a theatrical workshop setting to educate students on boundaries and consent in their own relationships. Consent and boundary setting can be challenging topics to discuss without raising personal, internalized triggering events. Using written work, like Shakespeare’s plays, creates an initial barrier between an individual and their prior embodied experience. Furthermore, for those unfamiliar with his work, Shakespeare’s dialogue can be difficult to immediately grasp which offers some aesthetic textual distance between participants and their personal experience. This distancing with classical work provides a stylistic entry point to explore the concepts of consent. Using the scenes within the play that involve the four love relationships—Hermia and Lysander, Helena and Demetrius, Theseus and Hippolyta, and Titania and Oberon—students can explore consent-based practices and boundary setting.

Utilizing A Midsummer Night’s Dream as a vehicle to break down and explore consent creates an aesthetic barrier between the workshop participants and potential personally activating or re-traumatizing experiences. The workshop involves a “no contact” rule during scenes that leaves physical distance for participants' comfort and exploration. There is the physical barrier of holding a script in one hand while reading, letting the participant avoid physical eye contact and engage with the text. Shakespeare’s Early Modern English, which can be challenging for contemporary audiences to analyze, offers a third barrier for participants to separate themselves from scenarios in the play.

This paper has two objectives. The first is to examine current practices in consent-based methods of undergraduate actor training. This literature review is necessary because intimacy choreography is a budding specialty in performance arts. The second goal is to outline the workshop experience and its uses in both boundary setting and coordinating intimate relationships in students’ daily lives. Working on two student-led productions during the Spring 2022 semester–John Lyly’s Gallathea and William Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar–I noticed a level of consideration and attentiveness for the cast and crew in the creative process that was missing from other department productions. I wanted to create a workshop that offers tools for communicating boundaries in productions, coursework, and students’ everyday lives. I developed the workshop discussed in this paper was crafted to be used among my peers—undergraduate and graduate students at the University of Colorado Boulder—to spread awareness of consent-based performance practices.

Current Practice

In their article, “Evolution of Consent-Based Performance,” Dr. Amanda Rose Villarreal (2022) notes the “documentation around this field has itself created a certain power imbalance” (6). They remind us that some voices have “become very prominent” as the field has grown, while others who have been practicing methods of boundary setting and intimacy work before terms like “intimacy choreographer” were used “have gone unnamed” (6). In a field that is still expanding, it would be remiss on my part to not mention the prominent documented and publicized voices and also acknowledge the unpublicized voices that have pushed intimacy and consent practices forward.

Intimacy and consent-based practices were born out of a need for cultural change around the discussion of boundaries and trauma prevention. Sarah Mantell says in their article, “Touch the Wound, But Don’t Live There" that “I believe the same things the profession does, somewhere deep in an unbudgeable part of my brain: that truly brilliant work is the work it harms us to make…that I make my best work when I am at my worst” (Mantell 2021). There is danger in untreated harm as its effects can be cyclical, and it continues even when a project or theatrical company ends. Carrying trauma in order to create “truly brilliant work” implies that we either have to stop making great work to heal or make the sacrifice of destroying ourselves as artists to make something brilliant. The promotion of care and consent-based practices can aid in breaking the cycle of harm, whether in artistic organizations, classrooms, or the everyday lives of university students. Theatrical Intimacy Education was founded in 2017 with the purpose of giving artists the tools to “ethically, efficiently, and effectively stage intimacy, nudity, and sexual violence” (“About: Mission” n.d.). The organization is made up of many artists skilled in various forms of consent-based practices and vocabulary. The focus of these artists is “cultural change, not just choreography” to better equip directors, artists, and teachers for tackling intimate work and creating space for consent.

Pace and Rikard are prominent, documented practitioners in the consent-based field who developed vocabulary and tools to assist directors, choreographers, actors, and teachers working with intimate scenes. Their artistic methods are not only invaluable in theatrical settings but also in workshop spaces designed to teach boundary establishment and facilitate exploration of intimate scenes. In her publication, Staging Sex,Chelsea Pace (with contributions from Laura Rikard) holds three main ideas for communication and boundary practices: creating a culture of consent, desexualizing the process, and choreographing scenes (Pace, 2020). Creating a culture of consent is meant to “normalize ‘no’” in response to a direction or choreography that makes an artist uncomfortable for any reason; creating a space where there is no hesitation to ask questions or voice concerns is the goal (Pace, p. 10). Desexualizing the language of an intimate scene means instead focusing on describing the actions for a scene (Pace, p. 11). Choreographing a scene prevents crossing boundaries and ensures there is no confusion about the direction of the scene (Pace, p. 12).

Power is always present in the room, whether wielded by a director, teacher, or facilitator. Pace’s ideas create a foundation that works in any room and with any group when discussing boundaries or working an intimate scene. Laura Rikard’s 2017 article “Working on Intimate Scenes in Class” echoes ideas later stated in Staging Sex. Before beginning any work on a scene, the students should face each other in the space and observe each other neutrally. Then they can proceed to establish boundaries with verbal comments and visual cues. For example, a student might say they are okay with touch on their forearm and visually indicate it by touching or sliding their hand along the area that is permissible to touch. A space or scene should never be left with unanswered intimacy questions after rehearsal; students should be in agreement regarding the action that will be taking place and aware of each other's boundaries. This beginning process can be utilized outside of a theatrical classroom in everyday boundary practice for people and their relationships. They may take a moment each day to indicate where they are comfortable with contact or inform their partner of new boundaries or boundaries that may no longer apply. A notable guideline to follow is presented by Tonia Sina in her article “Safe Sex: A Look at the Intimacy Choreographer,” in which she states that “students should never be rehearsing without a third party present” (Sina 2014, 14). A third party, such as a teacher, maintains the “integrity” of a scene and reinforces the reality of the classroom; it is a scene being rehearsed with an audience. Without third party oversight, it is easier for a student to slip out of character so that the scene suddenly activates personal involvement and triggers. Facilitation is important while engaging in consent-based practices and intimate scenes, whether for the classroom or a workshop.

Theatrical methods have uses outside the classroom for trauma-based needs. In the article, “A Trauma-Informed Analysis of Monologues Constructed by Military Veterans in a Theater-Based Treatment Program,” Alisha Ali, et al. notes that artistic methods may be used to help veterans process heightened emotions and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms after returning to civilian life (Ali et al. 2020). The program consists of a small group of three to twelve veterans who come together for ten weekly two-hour sessions. The group first analyzes Shakespearean war monologues; later, participants write their own individual monologues, trade them with each other, and perform the pieces in front of an audience of family and friends. As Ali points out, the “engagement in the arts, when implemented in a group format, can be a form of human connection that facilitates openness to each other and to oneself by encouraging creativity and self-exploration” (Ali et al., p. 259). Instead of using traditional talk therapy methods, the theater-based treatment crafts an emotional outlet, avoiding the military stigma of weakness for seeking help for psychiatric illness. The “narrative processing” used in the treatment helps build an external, written “representation of self” that the veterans can look at from a “safe aesthetic distance” while searching for meaning in their own words (Ali et al., p. 264). The “narrative processing” creates a barrier between reliving trauma through talk therapy and textually analyzing trauma through personal writing and communal performance. There is no guarantee that using Shakespeare’s text will prevent a traumatic reaction, but the well-chosen words of a play may help distance an individual’s past intimate experiences as the individual watches another participant of the program perform the piece.

I will end with a reference to a notable moment in the Zoom discussion, “Queering Casting and Authentic Representation,” during which casting director Charlie Hano said, “making art should not hurt you. If you were told to suffer for your art, you were lied to” (Ring of Keys 2021). Enduring harm is not sustainable, either in theatrical processes or in daily the life of students and artists. Theater-based and consent-based practices can extend beyond the performance world and into the personal lives of students for the betterment of their relationships.

The boundary workshop consists of four core components: a warm-up, a scene work portion, a discussion of the scenes, and a cool down

Workshop Methodology

Summary & Components

The boundary workshop consists of four core components: a warm-up, a scene work portion, a discussion of the scenes, and a cool down. Ideally, this workshop is three hours in length with ten to fifteen participants. The time required can vary depending on the ways in which participants engage with the layers of Shakespeare’s text; however, the following layout is based on a three-hour structure. The first fifteen minutes provide time for people to arrive, mingle, and ease into the material. Thirty minutes are dedicated to the warm-up, including activities exploring verbal and non-verbal consent practices. Two hours can be taken for delving into relationship scenes from Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, which includes acting scenes out, discussing key concepts, and trying these scenes again with new context. The final fifteen minutes should be taken for a cool-down and a re-energizing game.

Maybe final sentence instead: Facilitators should devote the final fifteen minutes to a cool-down exercise and a re-energizing game.

Warm-Up Exercise

The warm-up physically prepares the body and allows time to express verbal and non-verbal bodily needs while in the workshop space. During the stretching and bodily warm-up a summary of the play is provided.

● After stretching, the group takes a pause. Participants stand in a circle and observe each other to become familiar with each other’s presence in the room. This is a practice introduced by Laura Rikard to handle intimate scenes in an acting class (Rikard n.d.).

● After the observation phase, participants brainstorm ways to affirm a “no” response without using the word “no.” Examples include: nay, nope, not now, never, hardly, certainly not, of course not, I’d prefer not to, no dice, not interested, I need space, etc.

● In the second portion of the activity, participants find ways to physically embody a “no” response. These may include: backing up, stepping sideways, shaking one’s head, holding one’s hands up, and so on.

● The final activity aims to provide a playful entrance into the workshop’s main material. The game, “In the Woods with Puck,” explores experiences of consent and feelings surrounding boundary over-stepping while in a safe environment. One participant assumes the role of Puck in the woods while the other participants act as humans who are lost. If Puck approaches someone, they must freeze. Puck then models a position that this participant must assume and remain frozen in. While Puck does this, the other participants can roam freely. Once Puck has shaped more than half of the participants into frozen statues, the workshop facilitator may call for a switch; a new Puck is assigned, and all formerly frozen participants regain freedom of movement. There should not be any physical touch involved in the game. The purpose is to maintain distance while experiencing the emotional reactions of being shaped or defined by another person. How does a participant recognize a specific boundary in their body? Participants can step away from the game and take a break whenever needed. Mobility concerns and physical needs can be established before the game starts to prevent harm to participants.

The Scenes: Preparation for Engagement

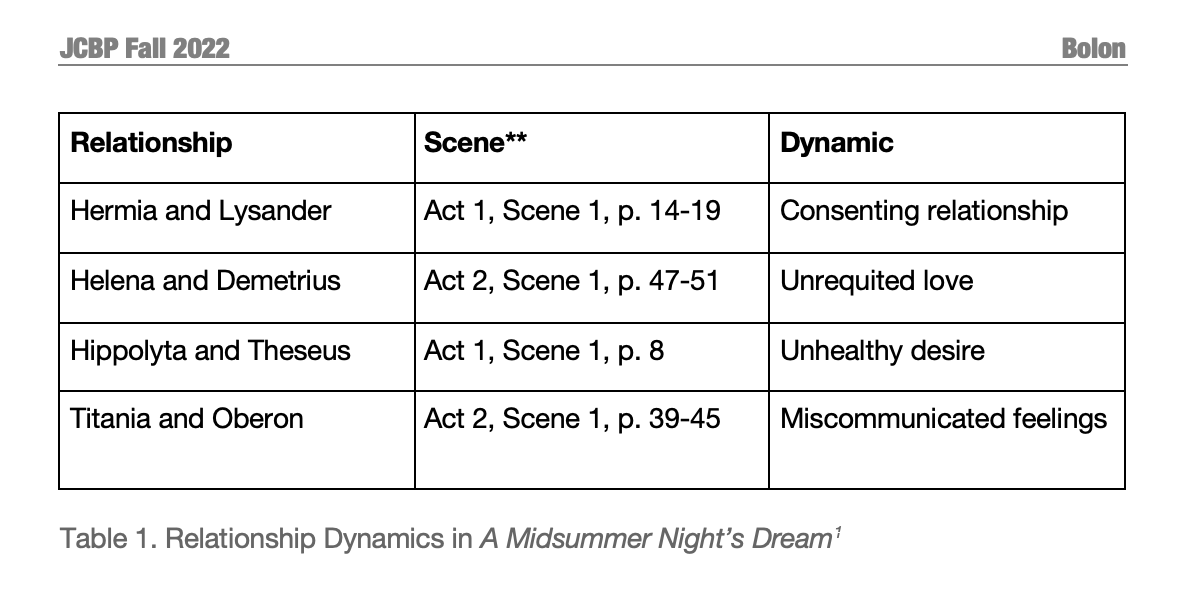

The main portion of the workshop, which utilizes Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, focuses on four scenes that showcase distinct relationship dynamics for participants to explore (Table 1). It is important to have participants both engage in the text and feel their own embodiment of “yes” or “no.” Therefore, participant volunteers involved will act out the scenes.

Table 1. Relationship Dynamics in A Midsummer Night’s Dream[i]

● Before reading the scene, volunteering participants should engage in touch confirmation and spatial needs recognition. This task can be accomplished by verbally informing each other of the areas they are comfortable with touch and/or nonverbally touching those areas. A moment should be taken to observe each other in space before starting. This practice is adapted from Chelsea Pace’s book Staging Sex, in the section on “The Boundary Tools” (p. 17-23). Unlike Pace’s tools, the process in the workshop does not lead to physical contact but instead recognizes one’s boundaries from a distance. The “no contact rule while reading” in scenes should be maintained. The goal of touch confirmation before reading is to allow participants to practice reaffirming their boundaries and familiarizing themselves with the action.

● The workshop facilitator offers context for the Shakespeare scene being read. The volunteering participants do a cold read of the scene without any movement. After the initial reading, participants pause for discussion.

● Questions about power and relationship dynamics inform the discussion. These might include: Who holds power in the scene? Who wants it? Who needs it? Who thinks they have it?

● After participants explore the power dynamics of the scene, the volunteers enact again. This time, they add in a directorial choice of who gets power. For example: one person speaks while the other can only offer non-verbal cues, one person wants to close distance while the other wants to create distance, one speaks with an urgent, caring tone while the other is monotone and cold, etc.

● After viewing the new directorial choice, another discussion takes place. The facilitator might ask: How can the characters achieve their goal and get the best outcome? Is it possible for them to get what they want without hurting each other or overstepping boundaries? Participants can offer thoughts and even recommend new staging to explore the dynamics of the relationship in a scene.

Relationship 1 - Consenting Relationship: Hermia and Lysander

Starting the main content of the workshop with Hermia and Lysander’s private conversation in act 1, scene 1 is ideal. The scene takes place after Hermia’s father, Egeus, seeks approval from the Duke, Theseus, for his daughter to marry Demetrius despite her interest in Lysander. After the other characters exit, Hermia and Lysander assure each other of their love in a private moment. Upon hearing confirmation that Hermia loves him, Lysander asks her to run away with him to his aunt’s home where they can marry (Folger, p. 14-19).

The scene explores a consenting relationship between two characters and offers a structural base for the other scenes to build on in the workshop. It is important to note who has power in the scene and consider whether Hermia can consent, given her only choice is to do what her father tells her or go with the man she loves. Playing with verbal and non-verbal cues in the scene is recommended. Participants explore the dynamic of a consenting relationship, discussing the ways they visually and verbally recognize consent within the characters’ interaction and response. They consider the ways in which that communication could be improved.

Relationship 2 - Unrequited Love: Helena and Demetrius

Working with the dynamic of Helena and Demetrius offers a perspective on unrequited love. In Act 2, Scene 1, Demetrius heads into the woods to pursue Hermia and Lysander. He loves Hermia, and after gaining Egeus and Theseus’s approval, he plans to marry her. Helena pursues him, having revealed the elopers’ plan to escape, as she desires Demetrius for herself (Folger, p. 47-51). During the course of their conversation, Helena expounds on the ways she loves Demetrius and the ways he hurts her by not loving her. Demetrius only acknowledges her to say he doesn't love her but Hermia, and he despises Helena’s continued persistence.

It is important to discuss Demetrius’s intentions as he ends their dialogue with “Let me go,/Or if thou follow me, do not believe/But I shall do thee mischief in the wood” (p. 51). Dissecting the potential threat and harm of “mischief” as well as the honesty of his love for Hermia can lead into a new read-through of the scene. While Demetrius is cold and ultimately threatens harm, Helena refuses to take “no” for an answer, ignoring all verbal and non-verbal cues to stop. Participants should discuss who truly holds power in the scene by the end, and how the dynamic could be resolved without causing harm to both parties, if possible. Participants will explore the dynamic of unrequited love and receiving “no” for an answer. They will discuss Helena’s nonconsensual pursuit of Demetrius and the ways gender changes their perception of that pursuit. Furthermore, they’ll consider Demetrius's threat if the pursuit is continued and recognize the issues with communication between both parties.

Relationship 3 - Unhealthy Desire: Hippolyta and Theseus

In Act 1, Scene 1, Theseus talks about his coming nuptials with Hippolyta. She responds, but her dialogue is short and offers comments on the “solemnities” of the union. Theseus states, “Hippolyta, I wooed thee with my sword/And won thy love doing thee injures,/But I wed thee in another key,/With pomp, with triumph, and with reveling” (Folger, p. 8).

After the initial reading, participants can discuss whether Hippolyta’s dialogue is happy, optimistic, or resigned. Facilitators might ask: If she was “won” through war and battle, does Theseus's promise to “wed thee in another key” matter? Is there any outcome that could give power to both parties in the scene? Directing the scene so Hippolyta can only provide non-verbal cues may reveal more about the dynamic than the words alone. Participants will explore the dynamic of unhealthy desire. They will discuss the definition of consent and whether it can be given in a relationship with an unequal power. Through this, participants can reaffirm or redefine how they view consent for themselves.

Relationship 4 - Miscommunicated Feelings: Titania and Oberon

In Act 2, Scene 1, Titania and Oberon meet after being separated due to a dispute over a changeling boy. As a result, Titania gives up Oberon’s “bed and company” (Folger, p. 39). Titania and Oberon argue who should be remorseful for their actions, bringing up old issues of both parties. The long, descriptive monologues can be shortened to reduce the length of the scene, but the conversation regarding why Titania has chosen to forswear Oberon is necessary. Despite Titania explaining her reasoning for holding onto the changeling boy, Oberon insists, “Give me that boy and I will go with thee” (Folger, p. 45). While there is back and forth dialogue, the information presented by either party is ignored and they both leave more disgruntled than before.

Participants can discuss potential strategies to resolve this issue: using non-verbal cues to ask for a pause or to softly interrupt, mirroring dialogue, taking time to process a response before answering, etc. Both characters hold power in the scene, so they try to dominate the other and overpower their dialogue. Facilitators might ask: Is it possible to establish boundaries and create pauses for listening? Participants will explore the dynamic of miscommunicated feelings. They will discuss personal listening techniques and leave with more options after sharing.

Cool-Down Exercise

The cool-down process of the workshop focuses on mentally distancing participants from the written text by re-engaging the body. This shift is accomplished using an adaptation of Viola Spolin’s “Kitty Wants a Corner” (Spolin, 2018). Renamed “Puck Wants a Corner,” the game maintains the same rule structure of Spolin’s work.

● Participants stand in a circle with one person in the middle.

● The individual in the center, Puck, approaches each participant individually in the circle saying, “Puck wants a corner!”

● The participant being asked the question asserts that they are not willing to leave their spot, or their “corner,” using a method of verbal or non-verbal communication.

● After being told “no,” Puck continues to move around the circle asking the same question. Puck does not have to conform to a circular pattern.

● While Puck talks to a participant, anyone in the circle can make eye contact and switch places; this part of the game requires affirmed, non-verbal communication of two participants. They can be next to each other or directly across the circle.

● If Puck notices a switch taking place, they can race to either empty spot and try to steal it. The person left in the middle without a “corner” is the new Puck.

The adapted game builds on the communication taught in the warm-up portion of the workshop, but it does so in the context of a children’s game that lets people play and laugh.

The workshop ends with a moment for participants to reflect on how they recognize consent as a whole and within their own bodies. A handout offered at the end of the workshop summarizes the activities explored: verbal and non-verbal affirmation options as well as ways to establish personal boundaries in a space with someone.

Discussion

The distinct parts of the workshop are individually important in crafting an integrated experience that helps participants gain new insights in boundary setting and relationship dynamics. The warm–up exercise is a critical aspect of the workshop and should not be shortened or overlooked if time runs short. The activities provided in the warm-up create familiarity among the participants and offer options for verbal and non-verbal affirmations to express consent. The dynamic of a room can change greatly depending on the familiarity of participants, so it is important to establish mobility concerns, physical injuries, and bodily needs before starting. The exercise for brainstorming consent and affirmation options is key to creating a sense of safety and trust, knowing that everyone in the group recognizes how a participant affirms or denies contact with their body. It also establishes the option for participants to explore new affirmations outside of those they already use. The exercise also provides a communal space where participants can try out verbal and non-verbal affirmations and “no” responses without judgment. It is the participants' chance to recognize the vocal quality of their own voice, the way it takes up space around other people, and the ways it changes depending on what affirmation they choose.

The “Puck in the Woods” warm-up game offers a light, energetic activity for participants to engage in before tackling the workshop’s main content. The activity can be prefaced with a discussion question, like: “How do you internally and physically feel when Puck sets your shape and position?” It should set up the participants for reflection while also leaving room for enjoyment of the game. It is important that the workshop facilitator never plays Puck. The game is meant to be kept light and playful; the facilitator is the guide who maintains the trust and safety of the space. If the facilitator involves themselves in the game and shapes the participants’ experiences, their presence can negate the established assurance of safety and boundaries by the sheer nature of the authority and power they hold in the room.

The exercise centered around Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night's Dream should be buffered by re-confirmation of boundaries and discussions held after the scenes. Reaffirming boundaries may start to feel repetitive, but the purpose is to practice the vocal tones and qualities required to assert those needs to another person. It also maintains the integrity of trust for the space. This boundary setting is important during the initial cold read and other read-throughs as the dialogue may contain motivation to make contact; therefore, knowing if and where contact is permitted is important. The workshop runs under the general rule of “no contact during scenes.” The cold read offers the mental space for participants to see the context of a scene without engaging in it emotionally or physically. When movement directions are added during later read-throughs, the participants are prepared to encounter what is in the scene. If necessary, participants can choose to step back for their mental well-being and have someone else do the reading. During discussion, participants acting in scenes should join the observing group and share their thoughts in a community circle. The discussion period is a place for definitions of consent and boundaries to be stretched and analyzed. The direction of the discussion may evolve based on engagement of the participating community and the guidance of the facilitator. Scene directions and re-interpretations will be different for every workshop, and it is important for the facilitator to adapt to the needs of the group. If the need is to focus more time on unrequited love, staying with Demetrius and Helena’s scene is advisable instead of pushing a group to move onto Hippolyta and Theseus.

The cool-down portion of the workshop is intended to physically let participants pull away from the content of the workshop and leave the space without emotional baggage. Therefore, the cool-down is a process of re-energizing the participants, letting them play, and having fun. The workshop offers a safe space for discussion; it should not re-traumatize or emotionally harm participants.

Some barriers will be encountered by participants during the course of the workshop. Juggling the need to hold a script, read from it, take directions, and move about the space will provide some barriers to the sensitive material in the play. The absence of physical contact in the exercise provides an additional barrier. These barriers contribute to the value of the workshop for participants since encountering and overcoming complex concepts allows people to begin to differentiate essential from extraneous factors in navigating their relationships.

Conclusion

The four interpersonal dynamics in William Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream are valuable in allowing students to explore boundaries and consent. Shakespeare’s Early Modern English creates an aesthetic distance for participants to avoid triggering experiences as they engage in the workshop’s activities. The scenes involving the four relationships are useful as vehicles to explore power dynamics, verbal and non-verbal cues, and conflict resolution in boundary setting. The workshop focuses on activities that let participants test verbal and non-verbal affirmations of consent, recognize vocal tone and assertion, and re-establish boundaries throughout the workshop. By the end of the workshop, participants grew in confidence after practicing their options for communicating, both verbally and non-verbally, and expressing their physical and emotional needs to another person.

References available in the PDF version of this article